Putting Food Equity on the Table

Amid substantial gaps in who has access to healthy, affordable meals, Dr. May Wang and other FSPH faculty, students, and graduates pursue policies and community partnerships that promote change.

AFTER SPENDING MUCH OF HER CAREER in the realm of maternal and child nutrition — striving to improve the life trajectory of children by focusing on pregnancy and diet during the first five years of life — Dr. May Wang decided to broaden the scope of her work with the onset of COVID-19, as it became clear that in Los Angeles and throughout the state, people of all ages were going hungry.

Wang, professor of community health sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, is part of a research team that found that in the pandemic’s first three months, more than 3 million Californians reported that their households went without sufficient food, an increase of 22% over the pre-pandemic rate. Equally alarming, research co-sponsored by L.A. County and published in 2021 found that 10% of the county’s households experienced food insecurity.

“We have long had significant disparities in who has access to sufficient amounts of healthy foods,” Wang says. “But with the pandemic, those disparities became much more glaring.”

While continuing her work on maternal and child nutrition, including a longtime collaboration with the largest local-agency Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, PHFE WIC, Wang has actively pursued collaborations with community organizations and policy groups that can reduce those disparities. In March of this year, Wang was named as one of two academics to serve on the technical advisory team of the Los Angeles County Food Equity Roundtable, a recently launched effort to track and address the county’s growing food insecurity challenge. Co-led by Los Angeles County and its philanthropic partners, the roundtable includes leaders from multiple organizations committed to addressing inequities in the current food system.

“Dr. Wang is extremely well-qualified for this work to support the roundtable’s mission and responsibilities to improve access to, affordability of, and consumption of nutritious food,” says Swati Chandra, director of the Food Equity Roundtable. “With her work on these issues, she brings tremendous expertise as both a nutritional scientist and public health policy expert to the team.”

Wide disparities abound across the spectrum of health measures, fueled by factors that include economic, educational, and environmental inequalities; racism and discrimination; and gaps in access to and quality of healthcare. But when it comes to food, Wang notes, these societal inequities are exacerbated by a host of additional factors, starting with the inefficiencies and injustices in the food system — how what we eat is produced, processed, packaged, transported, distributed, marketed, consumed, and disposed of. “The system is certainly fragmented, and a lot of people would argue that it’s broken,” Wang says.

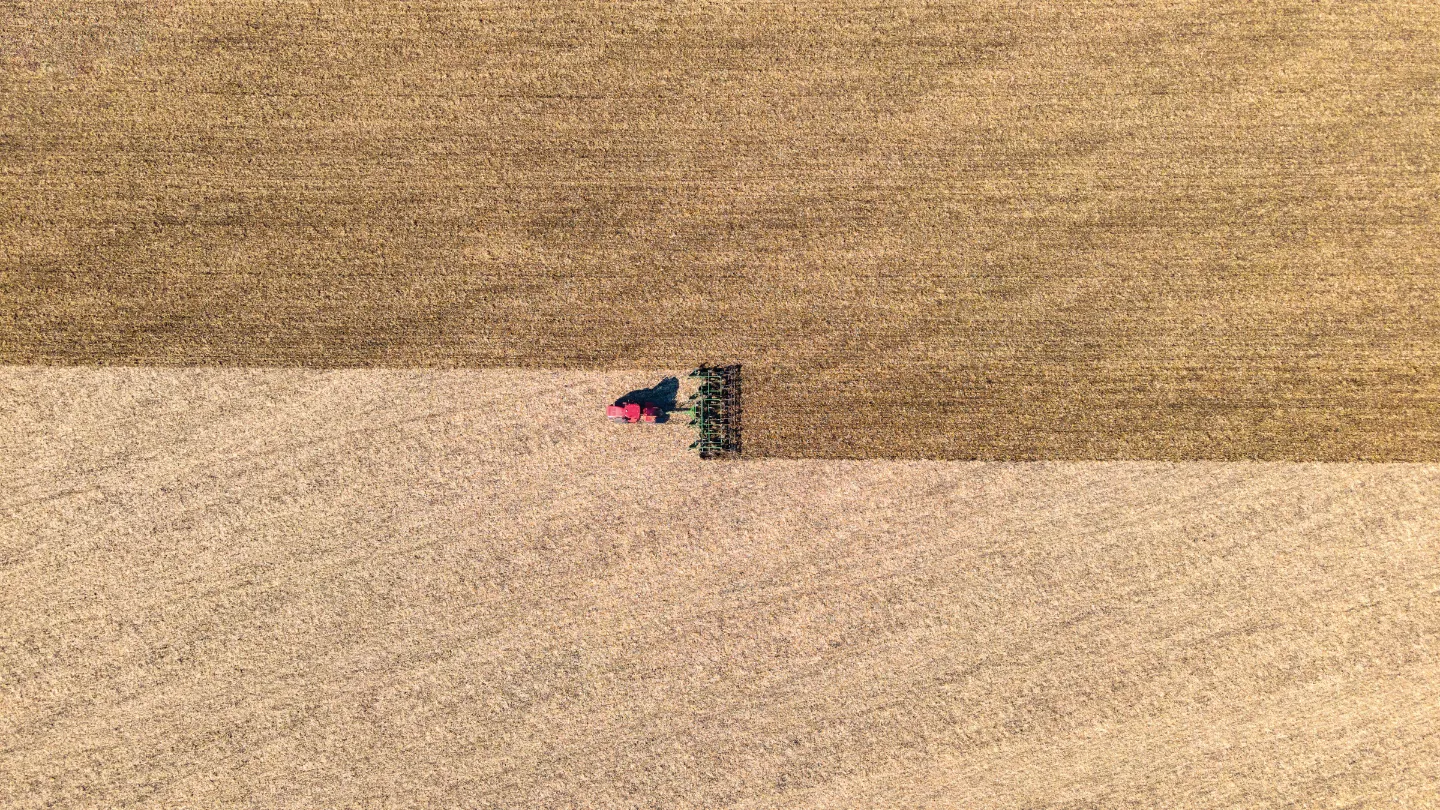

The inefficiencies of the system lead to disturbing levels of waste. In the U.S., up to 40% of the food produced is wasted — not eaten — according to the Natural Resources Defense Council; that failure was vividly displayed early in the pandemic by images juxtaposing farmers disposing of large amounts of food with long lines at food banks. Wang’s focus has been on the system’s injustices. She points out that in the U.S., decades-old policies incentivizing farmers to increase the production of crops that include corn, wheat, cotton, soybeans, and rice have contributed to the ready availability and lower cost of foods higher in fats and sugars, while the fresh fruits and vegetables essential to a healthy diet are less plentiful and more expensive.

Decades-old policies incentivizing U.S. farmers to increase the production of certain crops have contributed to the ready availability and lower cost of unhealthy foods.

The preponderance of inexpensive, unhealthy foods, along with the scarcity and higher cost of healthy foods, particularly in low income communities — so-called food deserts — help to explain why food insecurity and high rates of obesity can often be found in the same populations, Wang notes. “The government agriculture subsidies are part of the reason foods that are processed are cheaper than fresh food, even with the labor involved,” she says. Recently, the Biden administration announced plans to hold a White House Conference on Hunger, Health and Nutrition in September — the first White House conference on food since 1969. Wang sees this as a positive step toward policy changes that could address problems with the food system.

We have long had significant disparities in who has access to sufficient amounts of healthy foods. But with the pandemic, those disparities became much more glaring.

For food-insecure households, the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as Food Stamps and operating as CalFresh in California, is designed to assist families in purchasing food needed for a healthy diet. But, Wang notes: “Enrollment rates are low due partially to stigma, challenges in the enrollment process, and lack of information about the program. We have to bring diverse stakeholders to the same table to find effective ways to increase the reach of this program.”

One problem with SNAP, Wang explains, has been a burdensome application system. “You hear from many people that, with all the paperwork and in-person interviewing required, they feel demoralized by the end of the process,” Wang says. The process was expedited at the start of the pandemic — including the elimination of the need for in-person interviews — and benefits were increased, although it’s not clear how long those provisions will remain in place. Moreover, Wang notes, many low-income people who do obtain SNAP benefits continue to struggle to be able to afford a healthy diet, particularly in cities with relatively high costs of living such as Los Angeles.

Dismayed by the low SNAP enrollment rates among Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) immigrants in Los Angeles, Loan Kim (PhD ’11) partnered with the Los Angeles-based organization Asian Pacific Islander Forward Movement on a study to learn more about the reasons. An associate professor at Pepperdine University who completed her doctoral training at FSPH under the faculty mentorship of the late Dr. Gail Harrison, Kim concluded from the study’s interviews that many AAPI immigrants who qualified for the benefits preferred not to have to go through the enrollment ordeal.

“People had issues with an application process that caused them to have to miss almost a day’s worth of work in order to get themselves certified,” she says. “But the most profound thing we saw was that people felt this program, which was supposed to help, made them feel bad about themselves, and it wasn’t worth it to be interrogated. Programs like this tend to make it hard for people who are poor out of a fear they will try to cheat the system, when in reality that’s so rare — people who are struggling just to get food on the table and their kids off to school don’t even have the bandwidth for that. But considering these barriers, combined with the stigma associated with what used to be called Food Stamps, a lot of recent immigrants have a pride and dignity that prevents them from participating.”

Kim’s interest in the issue is informed by her own experience. She was born to a comfortable home environment in Vietnam, but her family was forced to flee during the communist takeover in 1975, eventually arriving in the U.S. with little financial means. “I saw how hard it was to live in poverty, but my father also said we weren’t going to depend on the system,” Kim says. As an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, she learned more about the health challenges of Vietnamese immigrants while working in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. Kim went on to become trained as a clinical dietitian, working in a hospital intensive care unit, before deciding she wanted to shift to a career in which she could work with immigrants in preventing the types of nutritionrelated illnesses she was seeing.

With both WIC and SNAP, we need to make sure it’s easier for people who need these services to access them, and part of that really comes down to how we as a society treat people who are living in poverty.

Kim has spent much of her career collaborating with the WIC program, a national effort in which states receive federal grants for supplemental foods, healthcare referrals, and nutrition education for the more than 6 million low-income pregnant women, new mothers, and their infants and children up to age 5 who are considered at nutritional risk. In late 2021, she and colleagues at the Nutrition Policy Institute worked with the National WIC Association to issue a report on WIC participant satisfaction and experiences during COVID-19. Kim notes that state WIC programs implemented changes during the pandemic, including virtual enrollment and recertification, increased voucher amounts, and greater flexibility in obtaining services. In a survey of more than 26,000 WIC participants across 12 states conducted in spring 2021, Kim’s group found that most participants were pleased with the changes and hoped that they would continue beyond the time when the pandemic is a concern.

Dr. May Wang (left), FSPH professor of community health sciences, serves as a technical advisor to the Los Angeles County Food Equity Roundtable directed by Swati Chandra (right).

“In the past, because of all the barriers, many people would drop off the rolls once they no longer needed support for their infant, and the challenge has always been how we help these participants continue to benefit from the program,” Kim says. “With both WIC and SNAP, we need to make sure it’s easier for people who need these services to access them, and part of that really comes down to how we as a society treat people who are living in poverty.”

The UCLA Fielding School has been instrumental in promoting healthier diets for WIC beneficiaries. In the early 2000s, research by Harrison and one of her doctoral students at the time, Dr. Dena Herman (MPH ’95, PhD ’02), now an FSPH adjunct associate professor and associate professor at California State University, Northridge, found that providing WIC recipients with vouchers for fruits and vegetables resulted in sustainable increases in consumption. The study inspired the first legislative change to overhaul the WIC food package, in 2009 — making it more healthful by adding fruits, vegetables, and whole grains while reducing the amount of juice, milk, and cheese. A 2019 study led by Wang; Dr. Catherine Crespi, FSPH professor of biostatistics; and Pia Chaparro (PhD ’13), one of Wang’s former doctoral students and now an assistant professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, found that these sweeping changes reduced the risk of obesity for 4-year-olds who had been on the program since birth.

Through her volunteer work serving meals at a shelter for people experiencing homelessness, Sarah Roth (PhD ’20) began to think about the limited nutritional options and lack of food choice for people who rely on the charitable food system, including food banks, pantries, and meal programs. Roth notes that many of these programs were developed in the 1980s as a response to an increase in poverty and hunger in the U.S. “The idea has been that there’s a lot of food waste in our system, and a lot of hungry people, so let’s make sure that food gets to them rather than being thrown away,” Roth says.

“It’s important that we find ways to raise the voices of people accessing [food banks and pantries] if we want to promote healthier eating habits.”

Over the years, though, more people have come to rely on charitable food. Feeding America, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization, reports that it serves 40 million people, including 12 million children, and for many, the need isn’t temporary. “Previously, these programs hadn’t been conceived as providing consistent nutrition supplementation,” Roth says. “They were to help someone who had just lost their job and needed to get back on their feet. But now, with inequalities becoming more entrenched, people rely on these systems more, and the thinking is that if this is going to be their regular source of food, we need to consider what foods are being accepted and distributed. There’s a well-established body of research showing that people who access food pantries and food banks have higher rates of chronic disease than the rest of the population.”

For her UCLA Fielding doctoral dissertation, Roth partnered with MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger on a national study assessing the influences on and implications of efforts to improve the nutritional quality of food distributed at food banks. Her findings, building off of the organization’s “A Tipping Point” report on opportunities to improve the nutritional quality of food bank inventory, highlighted some of the tensions among food, the environment, and waste. “There’s been an immense movement in the charitable food sector to make food healthier — to get fresh produce, dairy, and other perishable items into the food system, because those are the foods that people want to eat and people want to serve,” Roth says. “And yet, challenges remain, including both getting access to healthy food and what to do with unhealthy food. Do you just throw it away? And who’s to decide whether a brownie should go to the dump, or whether someone should be able to eat it?”

Roth, who is currently an associate research scientist with Providence Health & Services’ Center for Outcomes Research and Education in Portland, Oregon, points out that studies consistently indicate that people who use food banks and food pantries prefer fresh and healthy foods. “It’s important that we find ways to raise the voices of people accessing these systems if we want to promote healthier eating habits,” she says.

Traditionally, food banks and pantries have given out mostly canned and processed foods, and Wang worries that for the millions of children who rely on these programs for their sustenance, that cultivates taste preferences that will be difficult to change — setting them on the path to a high-fat, high-salt, high-sugar diet that increases their risk for obesity, diabetes, and other chronic conditions in adulthood. “We have to address all of these food inequities early in the life course, and that means providing healthier food options in supplemental nutrition programs and in low-income communities,” Wang says. “If you think about the public health benefits for our society in doing that, we have so much to gain.”ㅤ