Finding Justice

Hearing about the refugee journeys of her parents and their friends left Negar Omidakhsh determined to improve social conditions through research.

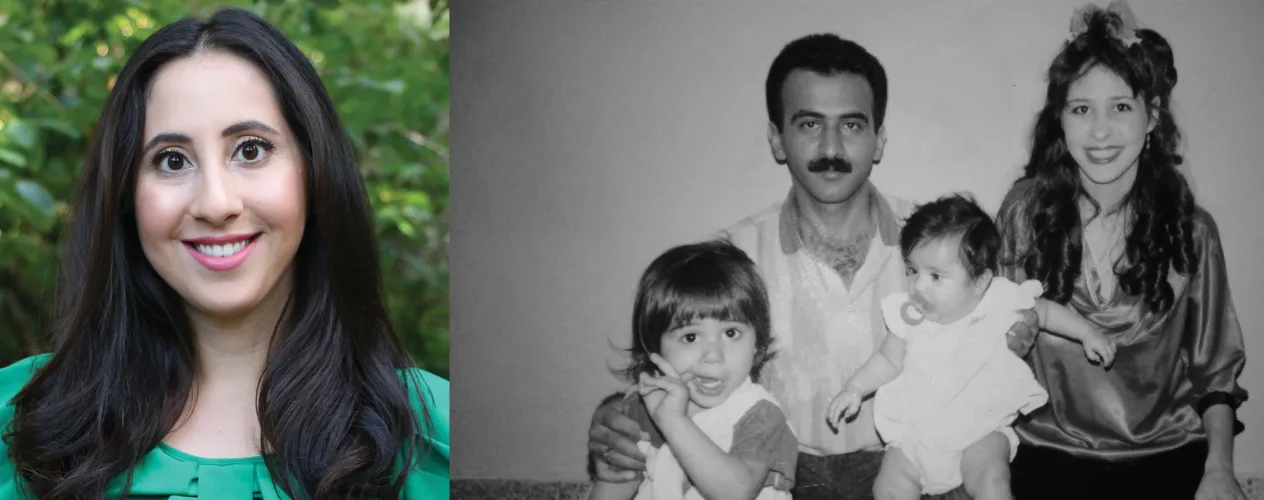

Negar Omidakhsh (PhD ’17) hadn’t yet turned 2 when her parents brought her and her older brother to Canada as refugees. They had fled Iran in the aftermath of the 1979 Islamic Revolution — losing almost all of their money to smugglers in the process — so that Omidakhsh’s father could receive a university education. Growing up, Omidakhsh watched with admiration as her parents worked tirelessly to learn a new language and obtain college degrees. She heard stories of the refugee journeys of her parents’ friends, each characterized by hardship, pain and the courage required to leave homes behind in the hope of a better future.

Growing up with a mother who was such an inspiring role model gave me an appreciation for the importance of equality and how that shapes all female generations.

These formative childhood exposures proved pivotal when it came time for Omidakhsh to consider what she wanted to do with her own life. “That understanding of adversity early on is what inspired me to pursue research aiming to alleviate the struggles faced by some of the world’s most marginalized populations,” says Omidakhsh, who is currently in her second year of the Hilton Postdoctoral Scholars training program, based in FSPH’s WORLD Policy Analysis Center.

While pursuing her undergraduate and master’s education at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Omidakhsh devoted significant time to advocating for refugee rights. She co-coordinated a well-attended series of talks at the Vancouver Public Library, where refugees could share their stories, then spent two years volunteering at a high-profile refugee law firm, preparing background research for families seeking to avoid deportation. Omidakhsh then came to the Fielding School for her PhD in epidemiology, with her dissertation focusing on maternal occupational exposures and childhood cancer risk.

In the Hilton program, Omidakhsh is learning state-of-the-art approaches to determining the most effective and efficient ways to improve social conditions for poor and marginalized populations at a global scale — specifically, how best to implement the Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015. Omidakhsh’s postdoctoral research has focused on policies and norms related to gender equality. Her first project looked at child marriage policies — an issue of personal interest to Omidakhsh, whose grandmother and mother married at ages 12 and 15, respectively. She found that in countries that implemented policies prohibiting child marriage, attitudes about domestic violence improved among both men and women. In June 2018, Omidakhsh co-led a workshop at the Girls Not Brides Global Meeting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, designed to assist advocates from around the globe in translating the findings into impact.

Omidakhsh says she has received invaluable training from the Hilton program in how to conduct independent research. She has also benefited from the opportunity to supervise FSPH graduate students in a systematic review of the relationship between global policy and women’s work outcomes. In all of her work, Omidakhsh is driven by a desire to improve the lives of women around the world. “I care about women’s health, their autonomy, the norms that shape who they become and the rights of their children, particularly if they are girls, to an education and a safe and thriving environment,” she says. “Growing up with a mother who was such an inspiring role model gave me an appreciation for the importance of equality and how that shapes all female generations.”