Viral Communications

Since early in the pandemic, the student-driven Multilingual COVID Information Project has used social media to spread clear and compelling messages to limited-English-speaking communities in Southern California.

When COVID-19 first began to spread across the U.S., Fielding School MPH student Tram-Elayne Nguyen worried about her parents, first-generation immigrants from Vietnam. “They were getting a lot of confusing information about what they should do and whether or not the pandemic was serious,” Nguyen recalls. “I could see that there was no clear, digestible, unbiased information for members of the Vietnamese community.”

Nathalye López noticed that despite the large population of Spanish speakers in Los Angeles, people like her parents with limited English-speaking skills were challenged to sort through messages that were sometimes conflicting, other times laden with medical jargon. “I also worried about undocumented people, who tend to have fewer resources,” López says.

Nguyen and López are among a group of Fielding School MPH students who, with guidance from FSPH faculty and input from public health agencies and community-based organizations, have led the Multilingual COVID Information Project (MCIP) — a campaign that uses social media and other platforms to provide public health messaging related to COVID-19, with an emphasis on reaching limited-English-speaking communities in Southern California. MCIP (www.covidinfo.ph.ucla.edu) delivers messages in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese.

MPH Student Jane Lee says her participation in the Multilingual COVID Information Project (MCIP) has taught her the importance of customizing communications to the intended population.

A lot of communities tend to be forgotten in emergencies. Sometimes it takes members of that community to make sure they’re protected, including identifying barriers to accessing the COVID-related resources.

As the pandemic unfolded, Dr. Anne Pebley, the Fred H. Bixby Chair and professor in FSPH’s Department of Community Health Sciences, found that among the students she advises — many of whom come from limited-English-speaking immigrant families — concerns about access to reliable information were all too common. “These students were talking with their family members about masks, hand-washing and physical distancing, but their families were also seeing all kinds of wild and inaccurate information,” Pebley says. “And what was accurate was often technical and not particularly easy to read.”

With funding from the FSPH Office of the Dean, Pebley enlisted several faculty colleagues to help support a mostly student-run initiative, in collaboration with TranslateCovid.org — a joint project of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center and the Fielding School (co-led by two FSPH faculty members, Drs. May Wang and Gilbert Gee) that compiles and shares in-language and translated COVID-19 resources in more than a dozen languages.

Nancy Nguyen was among the MPH students who embraced the MCIP. “With the onset of the pandemic, I wasn’t sure what role I could play as a public health student,” she says. “But I could see my family getting a lot of misinformation from both social media and their social groups — things like, if you cut up red onions and leave them around the house, it will kill the COVID virus coming in. I thought this would be a great opportunity to tap into my knowledge of the Vietnamese community and do my part."

Pebley believes the initiative derives its power from the fact that the students running it are bilingual, bicultural, and rooted in the communities they seek to reach. (Along with Tram-Elayne Nguyen, Nathalye López, and Nancy Nguyen, the core MCIP student members have included Tamar Galindo, Jane Lee, Aiyi Huang, Carlin Soos, Andreina Gómez, and Dome Lupac; other students have pitched in as needed.) “They have really taken the initiative to build this project and make it accessible to everyone,” Pebley says.

The MCIP students have also brought their creativity and social media savvy to the project. In regular meetings, MCIP students and faculty discuss long-term strategy as well as messaging for that week. The students craft social media posts, design infographics, and create videos, all of which are vetted by the faculty experts for their content. “At first, we relied a lot on re-sharing messaging from TranslateCovid.org, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and community-based organizations, in some cases translating or making it more digestible for our audiences,” Nancy Nguyen explains. “Then, once we built our social media presence, we brought more of our own creativity and personal experiences, thinking about how to reach people in fun ways.”

Much of the messaging has focused on guidelines for preventing COVID-19 transmission through appropriate mask-wearing, physical distancing, and hand-washing, as well as guidance tied to upcoming holidays and other events commonly celebrated in immigrant communities. As the vaccine rollout got underway, MCIP began a campaign to promote the immunizations and how they could be obtained, provide guidelines for post-vaccine life, and address vaccine hesitancy and myths. In addition to consulting with faculty, the students worked with community-based organizations and the communications team at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to fine-tune the messaging content and approach.

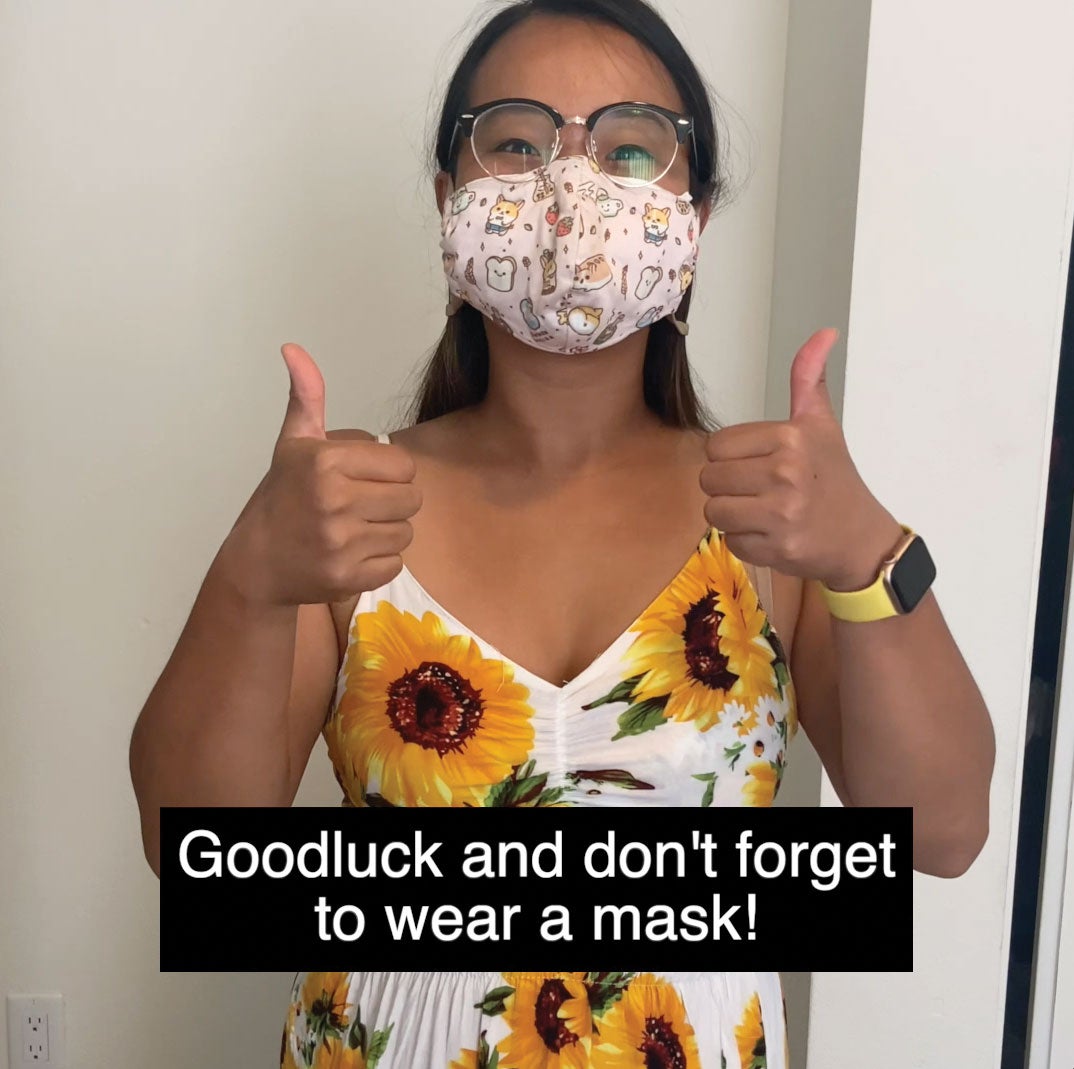

Inspired by TikTok's soaring popularity, MPH student Tram-Elayne Nguyen created videos featuring public health messages such as the one above, which addressed mental health and COVID-19 fatigue in Vietnamese, simplified Chinese, Korean, and Spanish.

“It’s been really helpful to connect with people who work closely with these communities and then develop content based on their input,” says Tram-Elayne Nguyen, who has led the way in creating videos posted on TikTok, the social media platform that has gained substantially in popularity over the last year, particularly among youth. The lighthearted videos, incorporating public health messaging into songs that are trending at the time, have covered topics ranging from guidance on mask-wearing, social greetings, and holiday celebrations to pandemic-related advice on self-care activities, virtual dating, and safe sex.

MCIP team member Jane Lee says the project has taught her the importance of tailoring communications to the intended audience. “There are no graphics that will be universally received in the same way,” she says. “I quickly found out that messaging that might be humorous to one individual might come across as bleak and/or irrelevant to another.” That’s true not just when it comes to different languages and cultures, but across social media platforms. For example, Instagram and TikTok tend to reach younger age groups, whereas Facebook is best for reaching older members of the targeted communities. Members of the MCIP team found, though, that while younger family members are more likely to be English speakers, they seek non-English social media posts that they can use to educate parents and other older members of their community.

“Social media is such a great way to reach various audiences because it allows you to test different methodologies at very little cost,” Lee says. “By creating a variety of posts, we were able to identify different elements of graphics that made them more appealing and engaging — whether it’s ways of framing a message, colors, shapes, pictures, or density of words.”

In addition to the social media campaign, through its website, MCIP provides printable infographics and social media posts for use by community organizations and health agencies. For interested community members who don’t use social media, the infographics and videos are delivered via email. The project has also collaborated with a student group at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health to make COVID-19 information available through text messaging for those who sign up.

Some of the MCIP students and faculty members have also presented in community settings. For Nathalye López, one of the highlights of her involvement with the project was the opportunity to give a COVID-19 prevention talk, in Spanish, at the high school she attended. “A lot of communities tend to be forgotten in emergencies,” López says. “Sometimes it takes members of that community to make sure they’re protected, including identifying barriers to accessing the COVID-related resources.”

It’s difficult to quantify how many community members MCIP has reached given the nature of social media, where posts are shared, retweeted, and forwarded, as well as the additional exposure the group’s content has received through publicity from organizations such as the Los Angeles County Medical Association, the Mexican Consulate in Los Angeles, and several social services agencies. MCIP also conducted a marketing campaign on Facebook targeted to limited English speakers that reached approximately 40,000 people.

The MCIP students say they have gotten as valuable of an education as they’ve given. “The project has helped me appreciate public health as a field that is multidisciplinary and inclusive of so many interests and endeavors, while solving critical issues to bring about positive change,” Jane Lee says.

“I’ve learned how powerful health communications can be, and the importance of clear, consistent, and timely messaging,” Nancy Nguyen says. “This isn’t going to be the only major public health event of our lifetime, and as public health professionals we can use this experience to promote health equity by reaching the communities that are, unfortunately, the most affected by a crisis such as a pandemic.”