Generating Evidence for Impact

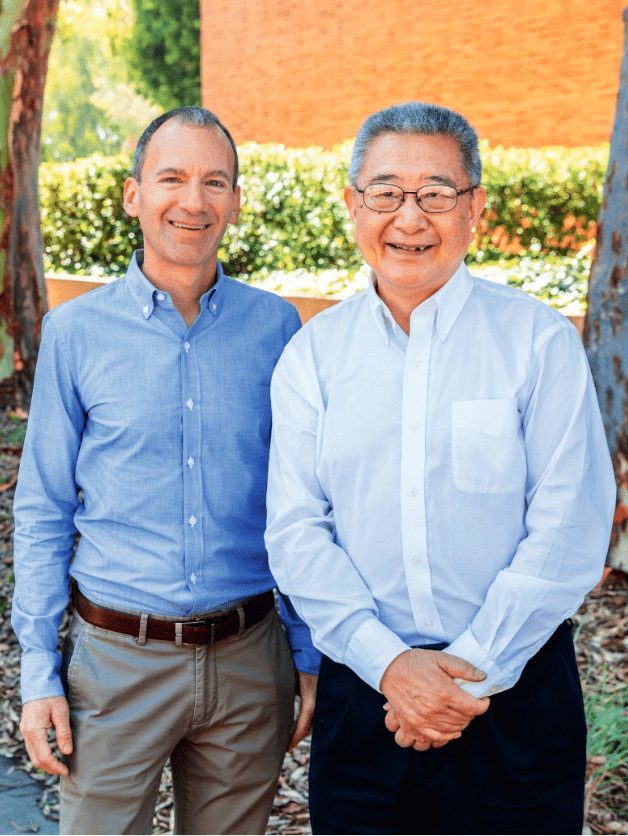

For more than six decades, faculty, staff, and students at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health have produced research findings that have advanced the health and wellness of populations by contributing evidence-based information leading to more effective and inclusive programs and policies. Today’s challenges are formidable — including the many-layered public health threats associated with climate change; the persistent, structurally driven inequities in health and healthcare; and the specter of future outbreaks and pandemics. UCLA Fielding’s associate dean for research, Dr. James Macinko (image, left), and his predecessor in the role, Dr. Zuo-Feng Zhang (image, right), recently discussed some of the strengths that have distinguished FSPH research historically, and how the school is poised for impact in the years ahead.

WHEN YOU THINK ABOUT UCLA FIELDING’S RESEARCH CONTRIBUTIONS OVER THE YEARS, WHAT STANDS OUT?

JAMES MACINKO: One remarkable aspect, when you look at the school’s contributions over time, is its breadth. Public health research here at FSPH covers everything from laboratory science and theory development to clinical trials, healthcare financing and delivery, program development, implementation and evaluation, community-engaged practice, and workforce training. Our faculty are actively involved in applying their research to policy and advocacy initiatives — often in collaboration with other FSPH faculty, other experts on UCLA’s campus, and community partners.

ZUO-FENG ZHANG: Another way of looking at UCLA Fielding’s wide-ranging excellence is that we’re in this new era often called “big data,” which requires very strict, rigorous study design and analysis techniques to ensure that we are reaching the right conclusions that can guide evidence-based policy and programs. That’s been a longtime strength of our school. And at the same time, we’re doing on-the-ground work: We have always had strong ties with communities, both locally and internationally, and many of our faculty work closely with community partners to identify research priorities, develop studies, share findings, and implement changes based on the results.

JM: A consistent theme of UCLA Fielding research over the decades has been to partner with minoritized communities in ways that address vulnerabilities while building on strengths. The school also has a history of studying public health issues broadly — looking at multiple levels of the environment, for example, to include factors such as workplace health and safety, how the built environment affects our health by promoting or limiting physical activity, how the local food environment can be associated with obesity risk, and how climate change affects agriculture and, consequently, the price and availability of healthy food.

WHAT ARE SOME INDICATORS OF THE SCHOOL’S RESEARCH SUCCESS?

JM: We have had steady growth in extramural funding. For a relatively small school, we do very well in that regard, both compared with other schools at UCLA and compared with other schools of public health nationally. Generally, about half of the funding we receive comes from federal grants, which tend to be highly competitive. But a good portion comes from state and local sources, which are also important — these often are for assessments requested by decision-makers. FSPH has invested in research infrastructure to help our faculty obtain large center and training grants, which help to amplify our work and provide funding for students.

ZZ: It’s also worth noting that our faculty are required to dedicate their time to teaching, mentoring, and service as well as research. Most of the larger schools of public health do not have this expectation. This enhances the students’ research experience. We bring our research into the classroom, and incorporate it in our training and mentoring. It also gives students more opportunities to become involved in the research.

JM: One of the major benefits that comes from our school’s success in obtaining large federal grants is that our researchers are often able to apply for what’s called a diversity supplement — creating additional projects for underrepresented students, which is a way to ensure that the research we’re doing best represents the communities we work with, and enhances the diversity of the public health workforce.

HOW DO FSPH RESEARCHERS MAXIMIZE THE IMPACT OF THEIR WORK?

ZZ: A big factor is the collaborative culture at FSPH. People here tend to work with other investigators in the school, but also with investigators in other health sciences schools and across the UCLA campus. As the nation’s top-ranked public university, UCLA has such a wide range of expertise, and since public health is a field that has always sought to work across disciplinary boundaries to effect change, we are able to leverage that strength better than most. There is also a determination at FSPH to make sure our research is put into practice. When I was associate dean for research, I saw more and more proposals that involved not just the science, but also the translation of that science to the community, or to support policymaking.

JM: I do think there is an ethos in our school not to conduct research in isolation, but to focus on dissemination and translation as well. We mobilize, and we make significant impact.

WHAT DO YOU VIEW AS THE BIGGEST GROWTH AREA IN PUBLIC HEALTH RESEARCH OVER THE NEXT DECADE?

JM: Climate change will become the driver for many of the public health challenges we see in the future. We will see greater impacts from wildfires, heat waves, and coastal flooding, all of which may contribute to trends in some chronic and infectious diseases. Transitions to clean energy will challenge our infrastructure and may also pose difficulties for major energy users, such as our healthcare systems. The continued migration of people from areas hit hardest by climate change will also drive the need to find better ways

to accommodate such climate refugees. Because the climate is complex, dynamic, and changes in relation to multiple factors, it requires big data and complex systems models with teams of scientists, which plays into some of our strengths.

WHAT MAKES YOU OPTIMISTIC ABOUT THE ABILITY OF UCLA FIELDING TO TACKLE CLIMATE CHANGE AND OTHER BIG PROBLEMS?

ZZ: COVID-19 showcased the problem-solving nature of our faculty, students, and staff. So many of them immediately pivoted to addressing this emergency — assisting in research, consulting on policy, and educating the public, both through the news media and in various community settings. We have brought in so many outstanding new faculty, which generates a great deal of energy and willingness to tackle new problems. At the same time, we have leadership within the school and the university that is encouraging and supporting that work. All of this leaves me optimistic.

JM: Public health has always been a field motivated by challenging, complex issues. Our faculty are diving in and taking on these big problems the way their predecessors tackled the problems of their time. And while today’s problems seem more complex, we now have more tools and knowledge that we can bring to solving them.

Faculty Referenced in this Article

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research