COVID-19's Toll on California's Latinos

In a series of studies, two UCLA Fielding School faculty members reveal that the ‘reward’ for a strong work ethic has been the highest death rates during the pandemic.

Latinos constitute 39% of California's population, and since March 2020 they have held many of the essential jobs that kept Californians well fed and functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, according to research led by two UCLA Fielding School faculty members, their “reward” has been the highest rate of COVID-19 infections and deaths in the state, with significant disparities between Latinos and non-Hispanic whites across all age groups.

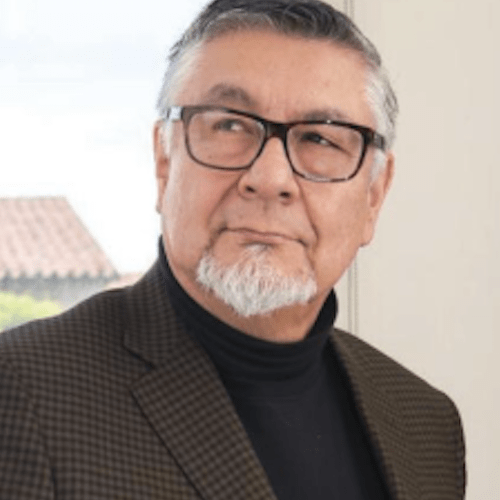

Many of the factors fueling these gaps relate to inequities in key social determinants of health such as employment, housing, and access to quality healthcare, according to the analysis of the researchers — Dr. David Hayes-Bautista (pictured left), FSPH professor of health policy and management and distinguished professor of medicine at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, and Dr. Paul Hsu (pictured right), FSPH assistant professor of epidemiology. These inequities are exacerbated by a “one-size-fits-all” approach in which protective measures have been issued during the pandemic that haven’t worked as well for the Latino population as for the non-Hispanic white population, Hayes-Bautista says.

In a report issued earlier this year, the researchers noted that COVID-19 death rates in the six months from July 2020 to January 2021 were between two and seven times higher among the state’s Latinos than among non-Hispanic whites, depending on the age group, with the disparities remaining relatively constant throughout the six-month period. Among individuals 80 and older, the death rate for Latinos was more than twice as high as for non-Hispanic whites; for those 65-79, it was more than four times as high. The Latino death rate was nearly six times the rate for non-Hispanic whites in the 50-64 age range; more than seven times the rate in the 35-49 age group; and more than five times the rate among individuals ages 18-34.

COVID-19 has had greater opportunities to infect Latino households compared with non-Hispanic white households in two ways, Hayes-Bautista and Hsu have found. For one, they note, a strong work ethic contributes to Latino households having more wage earners, on average, than non-Hispanic white households. This means that Latino households have had more adults leaving the house every day, who could then be exposed to coronavirus-positive clients and co-workers during work hours and bring the infection home. In addition, Latino families have more children per household than non-Hispanic white families, increasing opportunities to spread infections to family members even among those who are asymptomatic. Because they typically have more wage earners and more children, Latino households contain nearly one more person than non-Hispanic white households.

With more exposure to the coronavirus, coupled with less access to care, Latino essential workers have had higher case rates, and higher death rates.

Latinos are also overrepresented in many essential worker categories, from farmworkers who provide California’s food to construction workers who build the state’s houses, all while exposing themselves to the potential for infection. “Office-based wage earners have been able to minimize their exposure to coronavirus infection by sheltering at home and working online,” Hayes-Bautista says. “But Latinos are overrepresented in occupations that require wage earners to leave their homes and interact with co-workers and clients, such as farmworkers and grocery store clerks.” Hayes-Bautista notes that Latinos in the U.S. have created the equivalent of the world’s eighth-largest economy through hard work and larger families. Yet these very elements also make Latinos especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

Hayes-Bautista and Hsu have also concluded from their analyses that in many cases, the public health messaging regarding protective measures recommended to reduce exposures has been easier to implement in affluent, non-Hispanic white communities than in Latino communities. “Latinos are more likely to work in the types of industries that don’t pay high wages and don’t offer health insurance,” Hayes-Bautista says. “Those individuals can’t just unplug their laptops and work from home. They had no recourse but to stay at work, which helped to keep the state functioning and helped them feed their families.” He notes that in households in which one or more members need to isolate at home because of exposure to the coronavirus or a positive test, the public health guidance calling for one bedroom and bathroom per person isn’t generally feasible when multiple people are living together in a small apartment.

Latinos are overrepresented in many essential worker categories, including the farmworkers who provide California's food and individuals working in retail and at grocery stores.

Complicating matters was what Hayes-Bautista describes as a “preexisting disconnect,” relative to non-Hispanic whites, between the state’s Latino population and the healthcare system, stemming from less access to a regular source of healthcare and the shortage of Latino and Spanish-speaking physicians. Hayes-Bautista and Hsu point out that early in the pandemic, a physician’s order was typically required for individuals to receive COVID-19 testing, which made it difficult for those who were uninsured or couldn’t easily access a physician to receive a test, potentially contributing to more infections among people who were unaware they had contracted the virus.

In addition, many industries in which Latinos are overrepresented failed to adequately protect their employees. “Farmworkers, meatpacking workers, grocery store clerks, and nursing home attendants are also essential workers,” Hsu says. “But as they worked shoulder to shoulder in the fields or checked out customers’ shopping carts, they were not provided personal protective gear until late in the pandemic. With more exposure to the coronavirus, coupled with less access to care, Latino essential workers have had higher case rates, and higher death rates."

Hayes-Bautista believes it is imperative that public health leaders and policymakers draw lessons from the experience of California Latinos during COVID-19 and address shortcomings both for the current pandemic and for the epidemics and pandemics to come. “The strong Latino work ethic is seen in the fact that Latino households have more wage earners than non-Hispanic white households,” he says. “However, when they have to work more exposed to the coronavirus than white-collar workers, when they are paid very little for their hard work, when they are less likely to be offered health insurance, when they are less likely to find a doctor who can speak Spanish, it is no wonder that working-age Latinos have higher case rates and death rates than the general population. COVID brought a lot of preexisting inequities to a head."