Long-term exposure to ozone may increase risk of lung and cardiovascular deaths

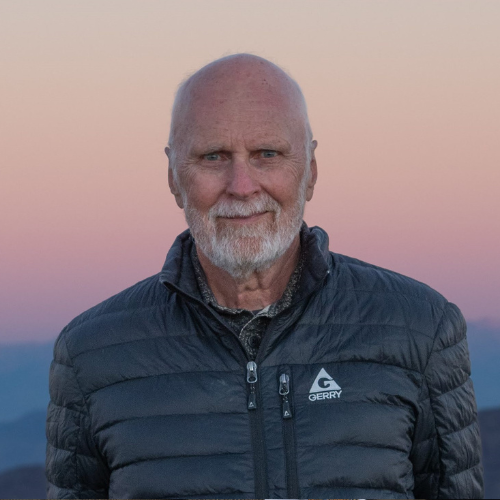

Dr. Michael Jerrett, FSPH Environmental Health Sciences chair, co-authored a study on long-term ozone exposure and mortality.

Adults with long-term exposure to ozone (O3) face an increased risk of dying from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, a study “Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality in a Large Prospective Study” published online ahead of print in the American Thoracic Society’s American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine suggests

Using data from a large U.S. study begun in 1982, researchers found that every additional 10 parts per billion (ppb) in long-term ozone exposure increased the risk of dying by:

- 12 percent from lung disease.

- 3 percent from cardiovascular disease.

- 2 percent from all causes.

Researchers said the increased risk of death was highest for diabetes (16 percent), followed by dysrhythmias, heart failure and cardiac arrest (15 percent) and by COPD (14 percent).

“About 130 million people are living in areas that exceed the National Ambient Air Quality standard,” said Michael Jerrett, chair of environmental health sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and study co-author. “While ozone has decreased in the U.S., the reductions are not nearly as big as decreases in other pollutants, and elsewhere in the world, ozone is a growing problem.”

The authors analyzed data from nearly 670,000 records in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study (CPS-II). Begun in 1982, the study enrolled participants from all 50 states; the average age at enrollment was 55. The researchers matched cause of death over 22 years with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control air quality data. During that time, more than 237,000 participants died.

Researchers took into account fine particulate (PM2.5) pollution, an established cause of premature mortality, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) pollution, which has been linked to premature mortality. They adjusted for 29 behavioral and demographic factors, including smoking, alcohol use, body weight, occupational exposures, diet, poverty and race.

Researchers found the association between ozone and mortality began at 35 ppb, based on the annual 8-hour average. They said that many communities are above this level, suggesting further reductions in ozone would have immediate health benefits. Jerrett added that reducing ozone, a potent greenhouse gas, would also provide future health benefits by reducing climate change.

Researchers were surprised by one finding: near-source PM2.5, largely attributable to traffic, was more strongly associated with death from cardiovascular disease than regional PM2.5, largely attributable to fossil-fuel burning and secondary formation of the particles in the atmosphere. With each 10-ppb increase in near-source PM2.5, mortality rate rose 41 percent, compared to 7 percent for regional source.

The study has some limitations, which include a lack of updated data on residential history, selection bias stemming from the exclusion of participants with missing or invalid residence data and a lack of historical ozone data.

But the findings still give a clearer picture of air pollution’s harmful effects, said Michelle C. Turner, lead author and a research fellow at the McLaughlin Centre for Population Health Risk Assessment in Ottawa, Canada and the Centre for Research in Environmental Epidemiology ISGlobal Alliance in Barcelona, Spain. A previous study with fewer participants, shorter follow-up and less detailed exposure models found ozone was associated with a smaller (4 percent) increase in respiratory deaths. In this larger study, researchers were also able to focus on specific causes of mortality.

“The burden of cardiovascular and respiratory mortality from ozone may be much greater than previously recognized,” she said.

The Canadian government, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, provided funding for this study.

Faculty Referenced by this Article

Dr. Hankinson is a Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and of EHS, and Chair of the Molecular Toxicology IDP

Associate Professor for Industrial Hygiene and Environmental Health Sciences

Industrial Hygiene & Analytical Chemistry