Fighting a Rigged System

When UCLA’s public health school opened in 1961, the U.S. civil rights movement was gaining momentum. That year, student activists launched freedom rides challenging segregation on interstate buses. Two years later, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famed “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The year after that, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law. And yet, nearly six decades later, the police killing of George Floyd forced a reckoning with the reality that for whatever progress has been made since the 1960s, entrenched structural forces fueled by racism, xenophobia, and more subtle forms of bias continue to plague our society — ensuring, among other things, continuing inequities in health.

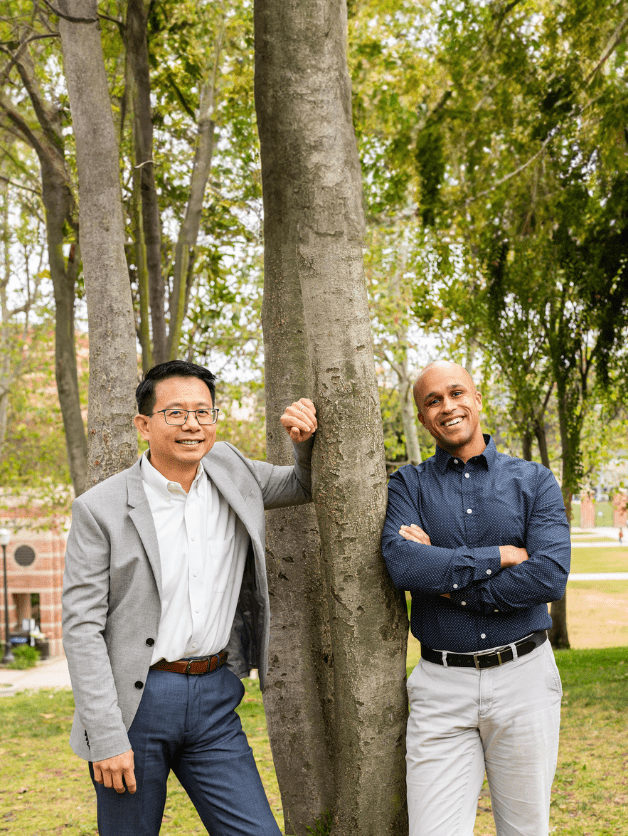

Only in recent years has the role of structural racism and other forms of discrimination become a major topic of public health inquiry and action. Dr. Gilbert C. Gee (image, left), professor and chair of UCLA Fielding’s Department of Community Health Sciences, was among the few focusing on these issues when he began his career; Gee, who joined the school’s faculty in 2007, studies racism and other inequities in social determinants of health among racial/ethnic and immigrant communities. Dr. Sean Darling-Hammond (image, right), an assistant professor of community health sciences and biostatistics who arrived at FSPH in 2022, is an attorney and public policy expert whose work seeks to identify the causes and consequences of racial bias, as well as the mechanisms that might ameliorate bias and its impacts.

WHAT DREW YOU TO UCLA FIELDING?

SEAN DARLING-HAMMOND: I believe combating structural racism requires structural change, and that structural change requires an interdisciplinary approach. What makes FSPH special is that it brings together scholars with expertise in both diverse methods — like randomized controlled trials, econometrics, and qualitative analysis — and diverse scholarly traditions like public health, psychology, sociology, and law. Scholars here marshal a truly interdisciplinary approach to generate the kinds of deep insights that can drive the structural change we need.

GILBERT C. GEE: One of the historic strengths of our school is its focus beyond the individual. As far back as the 1960s, Leo Reeder, a founder of what would become FSPH’s Department of Community Health Sciences, was a prominent medical sociologist interested in the forces of society that stratify health. He and many of the CHS faculty who followed — such as Steve Wallace, Carol Aneshensel, Margie Kagawa-Singer, and Anne Pebley — understood that while individuals are important, we need to look intensively at policies and structural inequities in our society.

WHEN DID STRUCTURAL RACISM AND OTHER FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION BEGIN TO BE VIEWED THROUGH A PUBLIC HEALTH LENS?

GG: Racism as a public health issue has been around a long time, but as a topic that people take seriously, it is a relatively new phenomenon. Scholars like W.E.B. Du Bois, and activists such as the Black Panthers, connected racism and health many generations ago. But only in recent years has it become more accepted in mainstream public health.

WHAT MOTIVATED EACH OF YOU TO GET INVOLVED IN THIS AREA OF STUDY?

SDH: In my experience as a legal practitioner, I saw how racial bias in juvenile institutions led many low-income Black and Latinx youth to be uniquely vulnerable to trajectories of harm, exclusion, and mental health challenges. That led me to work with other scholars to reduce racial bias through psychological interventions, and to explore the potential of intergroup contact to reduce bias at a population level.

GG: In the 1990s, when I was a grad student at Johns Hopkins, I was invited to give a talk to the master’s class on race and health and spent well over a month thinking about these issues. It was easy to describe racial differences in health, but what explained them? I went through the usual suspects — social class, access to care, culture — and none made sense when you considered the totality of the disparities. The only thing that made sense that we hadn’t grappled with was racism. That lecture launched my interest and my career.

WITH MORE INQUIRY, WHAT ARE WE LEARNING ABOUT THE PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF RACISM, AND WHAT ARE SOME OF THE MOST IMPORTANT QUESTIONS YET TO BE ANSWERED?

SDH: We now understand that racial bias drives inequity not simply because it makes us consciously decide whom we’ll give advantages to, but because it has a subconscious impact on how we respond in situations where there is discretion and ambiguity. That allows us to design and test interventions that shift mindsets and behaviors for teachers and parole officers in ways that reduce racial disparities in school discipline and juvenile outcomes, among other things, and can help create a more just society.

GG: We need to better understand individual experiences — the biological pathways whereby discrimination gets into the body and affects the brain and immune system. It’s also important to identify the policies and procedures within specific institutions, like medicine and policing, that create inequities. But at an even higher level, how do institutions collaborate to create this web of racial, gendered, disability-based, transphobic, etc., inequality that is so durable? The forces of equilibrium in our society are toward inequality, and we haven’t actually dismantled the structures that hold everything together.

SDH: In my work, I have sometimes looked at racism as being potentially intractable, and have evaluated interventions that work by sidelining or circumventing our mental recruitment of biased beliefs. But there is also interesting research that treats racial bias as a malleable construct. Especially during COVID-19, we saw how political rhetoric that stigmatized Asian individuals increased anti-Asian racial bias. But perhaps if rhetoric can increase bias, it can also reduce it. Perhaps if we articulate our views about racial groups and racial inequality in fruitful ways, we can reduce racial bias and animus at a population level.

IN WHAT WAYS HAS COVID-19 MAGNIFIED THESE ISSUES?

SDH: COVID clarified how structural racism can drive negative health outcomes. Even in Hurricane Katrina, when Black individuals experienced this natural disaster in a more negative way, it was partially because generations of Black people had to locate near levees, so you could point to historical factors. But COVID was different. No one was immune — and yet, because of structural racism, mortality and incidence rates were markedly higher for Black and Latinx people, and particularly in the counties where anti-Black bias was highest.

GG: COVID also helped put Asian American concerns in the national spotlight as a conversation point. Much of the time, Asian Americans are talked about as a model minority and used as a tool to argue there’s nothing wrong with American society with regard to inequality. That’s a false narrative, because Asian Americans encounter many disparities and inequalities. After COVID, more people are talking about Asian Americans in regard to civil rights.

WHAT IS IT YOU HOPE TO INSTILL IN YOUR STUDENTS TO HELP THEM SUCCESSFULLY ADDRESS THESE ISSUES?

GG: A major priority for me is to bring people to research as a career who have historically not been part of the research process. That requires shedding all the insecurities we are taught as oppressed people. We are taught not to believe in our own ideas, to be overly deferential. How do you persevere as an academic through disappointments and criticism? The best advice I have is to channel your emotions. The emotions that drive me are anger and love — anger at all the inequities, and love for the communities that have fought to provide the privileges I have, and hope to pass forward.

SDH: I agree with Gil — it’s helping students develop a growth mindset so they can overcome the imposter syndrome and internalized beliefs that often stop members of marginalized communities from engaging in this work for an entire career. That means making sure students of all backgrounds can gain the skills they need to help their communities thrive. It also means teaching them how best to collaborate with communities, which requires shedding assumptions, listening to what the community is experiencing, and working with, not working on.

WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES YOU HOPEFUL ABOUT PUBLIC HEALTH’S ROLE IN TAKING THESE ISSUES ON IN THE FUTURE?

SDH: We have people at FSPH who have invested their intellectual energy and capital into identifying, improving, and evaluating potential solutions to problems we once thought were intractable. That’s incredibly invigorating. On the flip side, we’re educating a generation of possibilists. They’re not asking what it is, they’re asking what can be. It’s been magical to watch students approach the world with this possibilistic lens. If we give them the tools to take that possibilism to wherever it can go, the sky’s the limit.

Faculty Referenced in this Article

Automated and accessible artificial intelligence methods and software for biomedical data science.

Assistant Dean for Research & Adjunct Associate Professor of Community Health Sciences

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Director of Field Studies and Applied Professional Training

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Director of Field Studies and Applied Professional Training

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Assistant Dean for Research & Adjunct Associate Professor of Community Health Sciences