Analysis: California malpractice cap on noneconomic losses associated with 16% more adverse events

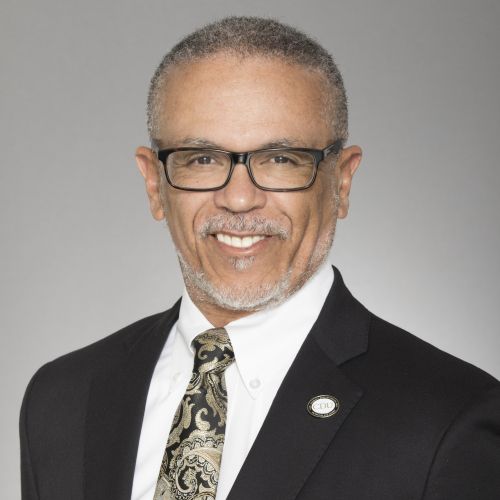

Study by Dr. Jack Needleman, professor and chair of Health Policy and Management, finds cap imposed in 1975 may be costing the state Medi-Cal program.

A new analysis from the University of California, Los Angeles suggests the state’s cap on noneconomic losses in malpractice cases has fallen far behind present-day values, and may even be associated with an increase in malpractice cases over the past five decades.

“The lack of adjustment to reflect inflation or the growth of household incomes is inequitable, because it lowers the real value of the reward — which in current dollars, could be as much as $1.5 million – six times the 1975 value,” said Dr. Jack Needleman, the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health’s Fred W. and Pamela K. Wasserman professor and chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management. “The second issue is that the cap, by lowering the risk of suit for malpractice, has also weakened the deterrent effect of risk of being sued on physician’s efforts to avoid malpractice.”

The study — “The California Malpractice Cap on Noneconomic Losses: Unintended Consequences and Arguments for Reform” — was published today by the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health's UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, where Needleman serves as a faculty associate.

An estimated 250,000 people die annually in United States hospitals due to medical error, and many millions more are harmed. Needleman’s work suggests the cap is actually associated with a significant increase in reported malpractice cases in California.

“The best available research suggests imposing caps is associated with a 16% increase in adverse events,” Needleman said. “Given this, it is likely that the repeal of a cap on noneconomic damages would increase attention to patient safety and lead to reduction of adverse patient events. These changes would be associated with cost savings to payers and patients, and reduced economic and noneconomic damages that improve the life and health of patients."

Needleman reviewed spending by the state Medi-Cal program associated with a narrow range of potential malpractice cases from “never events,” serious incidents defined by the state as wholly preventable or avoidable. Never events include objects left in patients after surgery, mismatched blood transfusions, or hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. In 2018, over a quarter of a million Medi-Cal patients experienced one of these “never events” and the state spent approximately $1.5 billion on these cases.

Many of these costs could be avoided if California’s malpractice cap was lifted or substantially raised. A 16% reduction in adverse events could mean savings to the state as much as $245 million annually, Needleman said.

The cap was adopted by California at a time of perceived crisis, when state legislators and others believed rising malpractice premiums and risk of lawsuit would encourage physicians to retire from practicing medicine and would raise overall medical costs through defensive medicine. No provision was made for indexing the cap level for inflation or growth in household income.

Between November 1975 and November 2021, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased by a factor of 5.03, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. If the cap had been adjusted based on CPI to maintain its purchasing power, its current value would be $1.257 million.

Given the cap addresses noneconomic losses, perhaps a better measure of the value of the cap would be the ratio of the cap to household income. In 1975, the cap of $250,000 was 19.5 times the median California household income of $12,778. If the cap had been adjusted to maintain the ratio of value to household income, its current value would be $1.5 million.

“That is six times the difference,” Needleman said. “In effect, someone who suffered in a malpractice case in the 1970s received much, much more in compensation, in a relative sense, than someone suffering the same injury today.”

The key argument for a cap on malpractice awards is that the caps lower malpractice risk and premiums. The lower premiums and lower risk reduce practice costs, reduce the incentive for defensive medicine such as unneeded diagnostic testing — which increases overall health care costs — and reduce the incentive for physicians to leave practice.

“Imposing a cap on awards also reduces the incentive to avoid malpractice,” Needleman said. “If the incentive to reduce malpractice is weakened, and malpractice rates increase, this raises the potential costs to patients and insurers, as well as increasing potential noneconomic losses for patients.”

Assessing the magnitude and impact of the loss of deterrence associated with a cap or other tort reforms is challenging. Malpractice, while economically and personally significant to the families experiencing it, is rare, and records in the United States are often limited by states.

However, Needleman said the most detailed research suggests state adoption of caps on noneconomic damages in medical malpractice lawsuits is associated with higher rates of preventable adverse patient safety events in hospitals, estimated as a 16% increase in these adverse events.

“The economic and noneconomic losses for patients and their families from malpractice can be significant,” Needleman said. “Beyond these, there are substantial costs to the state in Medi-Cal and medical payment for state and local government employees that would be reduced by raising or eliminating the cap on non-economic losses in malpractice.”

Methods: The inflationary element of this analysis is based on federal and state records, including from the California Legislative Analyst's Office, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the United States Census Bureau. The estimated costs and savings elements are derived from study of some 40 datasets, going back to 1991, and from across the United States, with statistical analysis to determine the potential benefits in California.

Funding: There was no external funding for this study.

Data availability statement: The data presented in this policy paper are available from the state of California Medi-Cal program.

Citation: Needleman J. 2022. The California Malpractice Cap on Noneconomic Losses: Unintended Consequences and Arguments for Reform. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, founded in 1961, is dedicated to enhancing the public's health by conducting innovative research, training future leaders and health professionals from diverse backgrounds, translating research into policy and practice, and serving our local communities and the communities of the nation and the world. The school has 761 students from 26 nations engaged in carrying out the vision of building healthy futures in greater Los Angeles, California, the nation and the world.

Faculty Referenced by this Article

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research