Elimination of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate linked to increase in uninsured, report says

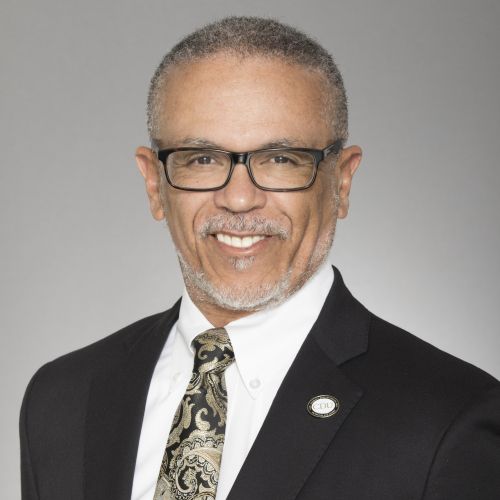

Research co-authored by Dr. Arturo Vargas Bustamante found that Latinos saw an increase in the probability of being uninsured.

UCLA RESEARCH BRIEF

FINDINGS

Research co-authored by Dr. Arturo Vargas Bustamante and Dr. Dylan Roby, both UCLA Fielding School of Public Health professors of health policy and management, found that U.S. Latinos saw a 5% increase in the probability of being uninsured after the elimination of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate.

The research letter, published by the Journal of the American Medical Association's JAMA Network Open, found that compared to other Americans, Latinos have higher probabilities of being uninsured, having to seek out emergency care, or delaying care due to increased costs after the elimination of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) individual mandate.

The cross-sectional study - "Changes in Coverage and Cost-Related Delays in Care for Latino Individuals After Elimination of the Affordable Care Act’s Individual Mandate" - analyzed National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2011-2019, and focused on data from the 2019 NHIS study to determine the effect that the elimination of the individual mandate that year had on coverage and access to care. Bustamante, Roby, and their colleagues found that Latinos saw a 5% increase in the probability of being uninsured, more than double the probability for Black and White populations in 2019. Latinos were also far more likely to delay care due to cost.

Both Black and Latino populations saw an increase in emergency department visits in 2019. While the likelihood of having a usual source of care increased during this time, there were still clear inequities between Latino populations and non-Latino Black and White populations.

BACKGROUND

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been associated with improvements in health insurance coverage and access to care. However, inequities persist. Studies show that while Latino individuals had significant gains in insurance coverage and access to care, they lag far behind non-Latino Black and White populations. Since 2010, several changes have occurred in the ACA because of legislative, executive, and court actions. It is important to continue assessing its progress in improving insurance coverage for all U.S. residents and to monitor health care inequities. Authors of this study include researchers from UCLA and the University of California, Irvine, as well as Drexel University, the University of Maryland, and the University of Miami.

METHOD

In this cross-sectional study, the researchers grouped 2011-2019 NHIS data by the period before the national ACA implementation (2011-2013), the start of the ACA implementation (2014-2015), the implementation of the health insurance mandate (2016-2018), and the year the individual mandate was eliminated (2019). The team limited the sample to participants aged 18 to 64 years. All results were nationally representative. Since NHIS is publicly available with deidentified observations, the Drexel University human research protection program deemed it exempt from institutional review board approval. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

IMPACT

By comparing observations from the period when the health insurance mandate penalty was in full effect (2016-2018) and the year the mandate was eliminated (2019), analysts observed that the Latino population had an increase in the probabilities of being uninsured, having an emergency department (ED) visit, and delaying care due to cost, despite an increase in the probability of having a usual source of care. However, usual source of care did not differentiate by types of care. A reversal in these health care equity indicators for Latino populations is evident from these findings.

The elimination of the ACA health insurance mandate may partially explain the increase in the probability of being uninsured for everyone. The authors suggest that for Latino populations, the possible chilling effects of the (President Donald J.) Trump administration’s public charge regulations and other policies restricting public benefits for immigrants could have played important roles. Policies to reduce out-of-pocket costs, including the continued availability of cost-sharing reductions and enhanced premium tax credits from the 2021-2022 American Rescue Plan, should be continued to address delays in care due to costs. A limitation of this study is that researchers did not look at state policy differences. Nevertheless, the findings of this cross-sectional study suggest that encouraging states to expand Medicaid and bolster the health care safety net to improve community-based services will also be beneficial in reversing health care inequities for Latino populations.

AUTHORS

The study’s authors include Bustamante, a senior fellow at the UCLA FSPH Center for Health Policy Research and director of faculty research at the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Initiative, and Dr. Dylan Roby, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health associate professor of health policy and management and faculty associate, UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, who also teaches at the University of California, Irvine; as well as colleagues from Drexel University, the University of Maryland, and the University of Miami. Dr. Alexander N. Ortega, of the Department of Health Management and Policy, Dornsife School of Public Health, at Drexel University, is the first author.

“Latino communities have long suffered from inequities in the American health care system,” Bustamante said. “We need to continue bolstering the health care safety net to address cost concerns and provide community-based services that are easy for Latinos to access.”

JOURNAL

The study is published online today in the peer-reviewed JAMA Network Open, an international, peer-reviewed, open access, general medical journal that publishes research on clinical care, innovation in health care, health policy, and global health across all health disciplines. JAMA Network Open is a member of the JAMA Network, a consortium of peer-reviewed, general medical and specialty publications.

FUNDING

This study was supported in part by grants R01MD014146 and R01MD013866 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) at the NIH (Dr Ortega).

by Paul Barragan-Monge

The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, founded in 1961, is dedicated to enhancing the public's health by conducting innovative research, training future leaders and health professionals from diverse backgrounds, translating research into policy and practice, and serving our local communities and the communities of the nation and the world. The school has 761 students from 26 nations engaged in carrying out the vision of building healthy futures in greater Los Angeles, California, the nation and the world.

Faculty Referenced by this Article

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.