Expanding the View

Through a big-picture perspective on how women can optimize their health, FSPH faculty are contributing to a new paradigm.

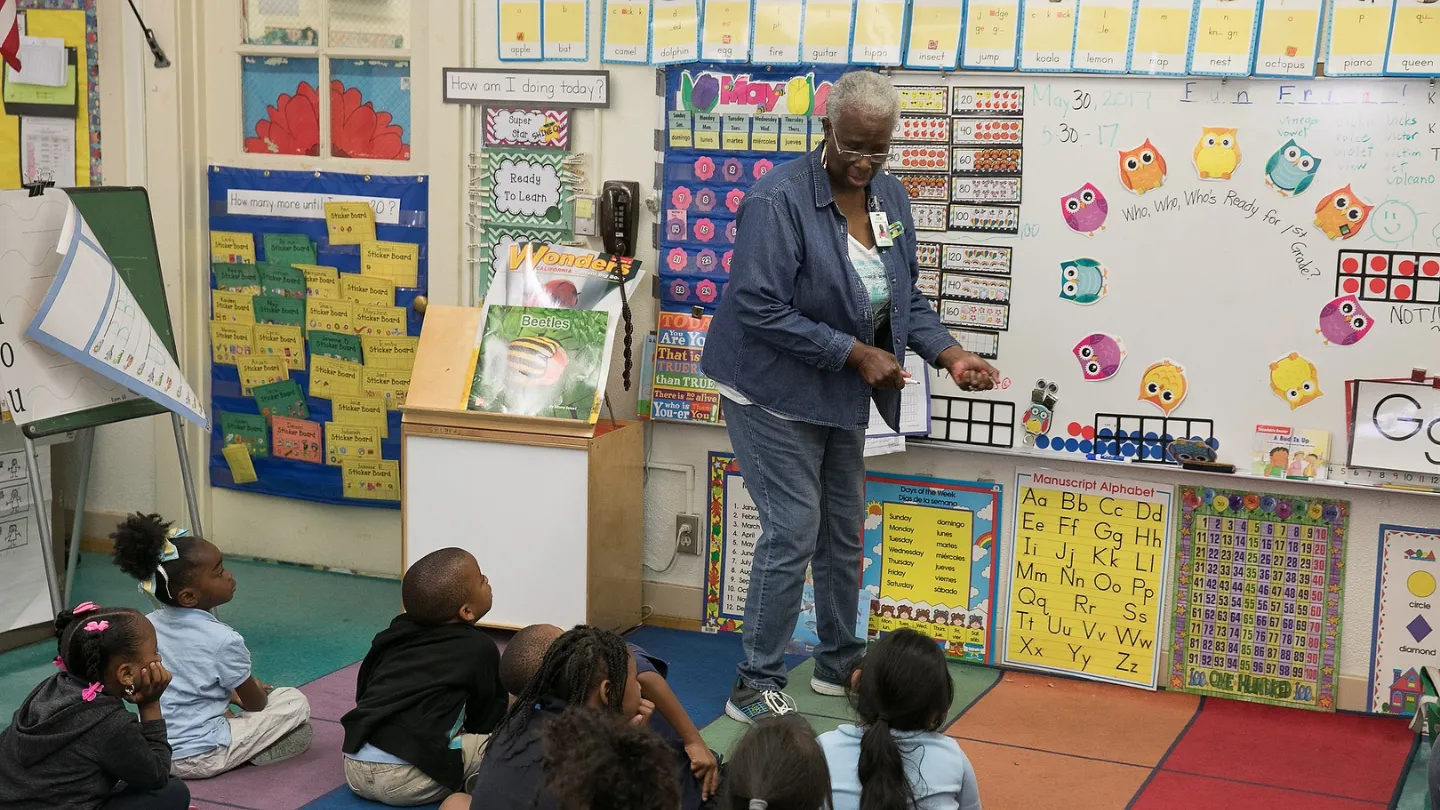

FOR THE TEACHERS IN THE LOS ANGELES UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT elementary school classrooms that participate in Generation Xchange (GenX), the middle-age and older adults who spend at least 10 hours a week providing academic assistance and support to struggling students are a welcome addition, to say the least. But for Dr. Teresa Seeman (MPH ’78), professor of epidemiology at the Fielding School and medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, who established GenX in 2014 after collaborating with Johns Hopkins University colleagues on a similar program in Baltimore, there is another side to the equation.

“We were interested in building new socially important roles for middle-age and older adults, given that this population is growing so rapidly,” Seeman explains. “With so many schools losing resources and looking for extra help, the idea was that these volunteers could contribute in a way that’s not only fulfilling, but also ends up being health-promoting for them.”

GenX trains adults ages 50 and older to work with teachers in kindergarten-through-third-grade classrooms on improving students’ skills in reading and math, as well as addressing behavioral issues. The middle-age and older adults, the vast majority of them women, commit to working in the same classroom throughout the academic year. The program currently has 45 volunteers assigned to four schools located in low-income Los Angeles neighborhoods.

We were interested in building new socially important roles for middle-age and older adults, given that this population is growing so rapidly.

In developing GenX, Seeman and her colleagues foresaw wide-ranging health benefits — social, psychological, cognitive and physical. “These middle-age and older adults are walking around, socially engaged with the kids and teachers, and involved in a meaningful activity that is cognitively stimulating,” Seeman notes. A study of the health impact on GenX volunteers produced the hoped-for results. By the end of the academic year, participants showed significant improvements in blood pressure and walking speed while losing an average of five pounds. Seeman’s team found reductions in inflammation — associated with risk for heart disease, cognitive decline and early mortality, among others — along with improvements in immune function. The volunteers also reported making significant numbers of new friends.

Seeman’s group is now studying the program’s impact on students’ academic performance and behavior; ultimately, she hopes this will lead to its expansion to other elementary schools in the district.

As the ranks of women living decades beyond retirement have increased — the 85-and-older population of women in the U.S. is now approximately 4 million — there is a growing need for meaningful roles that are engaging socially, cognitively and physically, Seeman notes. “What’s unique about GenX from a public health standpoint is that we attract people for reasons other than their own health promotion,” she says. “Our participants all say they like that they’re losing weight, but that the main reason they continue to do this is because of the kids.”

GenX is emblematic of a growing movement in public health to expand the paradigm to include strategies that enhance quality of life and overall well-being. “In the past, we’ve often tended to focus on the individual pieces — physical health, mental health, quality of life — but when you back up and start to look at health more holistically, it takes a different hue,” Seeman says.

Although the majority of breast cancer diagnoses occur in women in their 60s and older, as many as 25 percent of new breast cancer cases are in women younger than 50, notes Dr. Patricia Ganz, a Fielding School professor of health policy and management. For women in their 30s and 40s, she adds, the experience with the disease and its treatments is substantially different from that of older women.

Although the majority of breast cancer diagnoses occur in women in their 60s and older, as many as 25 percent of new breast cancer cases are in women younger than 50, notes Dr. Patricia Ganz, a Fielding School professor of health policy and management. For women in their 30s and 40s, she adds, the experience with the disease and its treatments is substantially different from that of older women.

“A woman diagnosed in her 70s has probably had friends who have had breast cancer. She may have already experienced other major health events or gone through them with a spouse,” Ganz says. “It can be very different for a young woman, who might also require more aggressive therapy that can be both disruptive and disfiguring, along with anti-hormonal treatment that can exacerbate symptoms as she enters menopause.”

With improved survival after breast cancer diagnosis, many younger women are living for decades after being treated for the disease. Over the last 30 years, Ganz, a medical oncologist, has been a pioneer in research on the long-term quality of life of breast cancer survivors. She has found that younger survivors experience the highest levels of symptoms that include depression, stress and fatigue, persisting for as long as a decade after their diagnosis. Yet, little research has been done on strategies to reduce the depression and manage the stress of this younger population.

Based on preliminary research to determine what might be most helpful for young women dealing with cancer’s after-effects, Ganz received funding for a pilot study of a six-week program of mindfulness meditation. The study found that in the short term, the mindfulness- based intervention reduced stress, depressive symptoms and inflammation. Based on those findings, Ganz, in collaboration with Dr. Julienne Bower, a professor of psychology and psychiatry/biobehavioral sciences at UCLA, is now in the second year of a five-year, multisite randomized clinical trial with colleagues at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins. The study randomly assigns 360 younger, post-treatment breast cancer survivors to one of two promising group programs, survivorship education or mindful-awareness practices, and compares each to a control group of women who will be offered the group program of their choice after the study follow-up period ends.

Psychosocial strategies that help people feel better are great, but if you can show the biological mechanisms that underpin the change, it’s much more powerful.

“We expect that depressive symptoms will improve among women in both intervention groups — whether it’s from information to help them function and cope better with the experience of the cancer or, in the case of mindfulness, learning techniques to address their stress — and that we will learn who might benefit the most from one approach or the other,” Ganz says. “In addition, although our study isn’t focused on formal psychosocial support, being in a group program with other young breast cancer survivors should be beneficial for these women, who would seldom encounter women their age with a history of breast cancer.”

In the past, many in medicine were skeptical about the efficacy of mind/ body interventions, but a growing body of evidence supports the benefits of mindfulness meditation and other mind/body techniques in reducing the symptoms associated with cancer and other chronic illnesses. Ganz’s group has been a leader in testing these approaches for breast cancer survivors. In previous studies, she has found benefits from yoga and tai chi in addressing symptoms of fatigue and sleep difficulties in survivors. Importantly, Ganz and colleagues have pinpointed biological underpinnings for these improvements. “Psychosocial strategies that help people feel better are great, but if you can show the biological mechanisms that underpin the change, it’s much more powerful,” she says. “Although our current study is mainly measuring behavioral symptoms, if we also find that the mindfulness intervention results in reduced inflammation — which we think may be associated with the fatigue, sleep disturbance or depression — that would be valuable information.

“Mindfulness isn’t for everyone, but given the rates of depression and anxiety in young adults, it can be a useful tool for those who tend to frequently worry and are easily distracted,” Ganz says. “We also believe the survivor education group, which teaches about healthy behavior and emotional distress, will be effective. The bottom line is that a 40-year-old breast cancer survivor with no other major health problem has many years ahead of her, so it’s particularly important to recommend effective strategies for both promoting wellness and potentially preventing a recurrence.”

As a social epidemiologist, Seeman has long been interested in how social factors influence health. Her early work examined the biological mechanisms by which social connections affect processes associated with aging, such as cognition and cardiovascular risk. Not surprisingly, Seeman learned that social influences affect a wide variety of biological indicators — blood pressure, inflammation, and glucose levels, among others — in significant but small ways.

Seeman’s research trajectory changed when she met Dr. Bruce McEwen, a neuro-endocrinologist at Rockefeller University in New York who conducted a series of studies in the 1990s that introduced the concept of allostatic load. “The idea is that our health risks are more effectively visualized as being the result of multiple biological factors that simultaneously influence health outcomes,” Seeman explains. “I realized that this was probably how social factors affect health — through impact on a slew of biological processes.”

Seeman collaborated with McEwen on some of the earliest studies of allostatic load — a cumulative index of problems across biological systems that was found to be closely associated with aging and predictive of the risk for cognitive decline, physical decline, heart disease and early mortality. Seeman also began studying factors that predict high levels of allostatic load, and discovered that they include low socioeconomic status and weak social networks.

“This points to the importance of promoting strategies that are upstream from the biology,” Seeman says. “Obviously, medication is necessary to bring down high blood pressure, but that’s not solving the problems elsewhere in the body. What’s truly needed are public health interventions such as improving the quality of neighborhoods, offering resources so that people’s lives aren’t as stressful, and providing opportunities for people to integrate socially and engage in ways that make them feel empowered. We know all of these things are associated with lower levels of overall biological risk.”

In the Generation Xchange Program established by FSPH faculty member Dr. Teresa Seeman, volunteers help students in low-income elementary schools while reaping significant benefits of their own.

When she began discussing the concept of allostatic load with Seeman, Dr. Dawn Upchurch, professor of community health sciences at the Fielding School, knew it was an area that she wanted to further explore; soon, she began to collaborate with Seeman.

Upchurch focuses on women’s health, with a particular emphasis on what women can do to promote wellness and well-being. She has recently turned to developing a healthy-behavior index — the combination of lifestyle practices and activities that are optimal for women’s health, especially as they go through midlife and beyond. In developing the index, Upchurch’s focus is not just on traditional health behavior strategies such as diet and exercise, but also on less traditional behaviors such as stress reduction, social engagement, coping skills, and activities that give women a sense of purpose and support. “We want to see if there is a combination of factors that might be most helpful for women, and if that combination differs depending on the population of women you’re looking at,” she says.

In addition to its association with accelerated aging and shortened lifespan, allostatic load provides an early indicator of the cumulative physiological wear-and-tear of stressful circumstances, making it an ideal marker for measuring the impact of behaviors designed to reduce that impact, Upchurch notes. Her research has found that allostatic load increases as women age, and that women who face discrimination and high levels of perceived stress experience higher rates of allostatic load increases. “We know allostatic load is one of the ways in which social and environmental stressors get ‘under the skin’ to affect health,” Upchurch explains. “Developing public health programs that assist women in positively coping with life’s stressors can also help to slow down the effects of aging.”

Based on these and other findings, Upchurch is interested in encouraging positive coping strategies for women, especially in midlife, which she notes is a particularly significant time marked by changing social roles, increased risk of chronic conditions, and transition through menopause. She has found that midlife women who engage in greater amounts of physical activity have significantly lower allostatic loads than those who don’t, independent of age or race. Other positive coping strategies might also help to keep stress levels — and allostatic load — in check. These include cognitive strategies, such as reframing the way one experiences negative events or situations. An optimistic attitude is associated with positive coping, as is a strong social network. Mindfulness meditation and other stress-reduction and relaxation techniques can also be effective, Upchurch notes.

“Allostatic load tends to be a subclinical measure — it shows up as a problem before people reach the point where they would be clinically diagnosed as having a chronic condition,” Upchurch says. “As a public health researcher, that’s exciting because it raises the potential for prevention strategies.”

Faculty Referenced in this Article

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

Dr. Joseph Davey is an infectious disease epidemiologist with over 20 years' experience leading research on HIV/STI services for women and children.

Dr. Anne Rimoin is a Professor of Epidemiology and holds the Gordon–Levin Endowed Chair in Infectious Diseases and Public Health.

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program