COVID-19 casts stark light on structural inequalities in California

Dr. David Hayes-Bautista and Dr. Paul Hsu have found that Latino Californians are among the hardest hit by the pandemic.

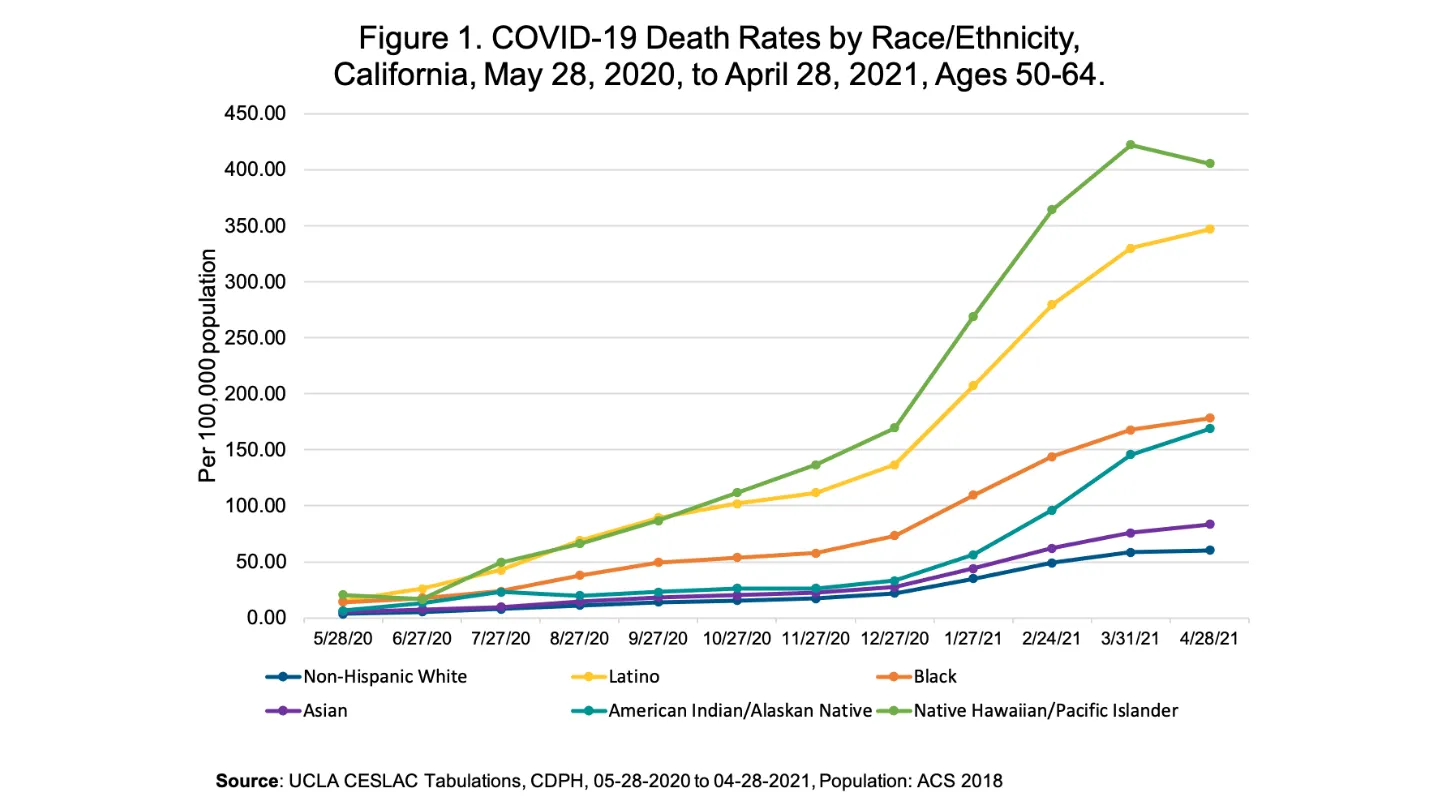

In a society without structural inequalities, the COVID-19 mortality curve for California would have been the same for everyone, with no difference between the state’s racial/ethnic (R/E) groups.

But the first pandemic year has cast a stark light on the various inequalities that are part of California’s social structure. Over those twelve months, all non-white R/E groups have had COVID-19 mortality rates many times greater than the non-Hispanic white (NHW) mortality rate.

“If everyone had had the same opportunities to shelter at home, use personal protective equipment, get tested, and see a doctor at the first possible symptoms, there would have been very little difference between the state’s R/E groups,” said Dr. David Hayes-Bautista, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health professor of health policy and management, distinguished professor of medicine with the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and director of the UCLA Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture (CESLAC).

The Latino death rate, for example, went from merely twice as high as the NHW death rate in May 2020, to nearly six times as high by April 2021. With some minor variations, all other non-white R/E groups showed similar, growing disparities, resulting in higher and higher death rates.

“For some time now, we have seen how different groups have different access to prevention and care. Three years ago, we reported that Vietnamese, other Southeast Asian, Filipino, and Spanish-speaking doctors were under- represented in the state’s physician workforce. And Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Latinos have higher COVID-19 mortality rates, compared to the largely English-speaking NHW group,” said Dr. Paul Hsu, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health assistant professor of epidemiology. Hsu noted that language was only one of many ways in which the state’s different R/E groups have unequal access to care.

“COVID-19 is a communicable disease, and some R/E groups tend to be in occupations and industries, such as agriculture and food service, that expose them more to contagion from co-workers or customers than white-collar workers sheltering at home in front of computer screens,” Hayes-Bautista said.

This disproportionate increase in mortality in non-white R/E groups reflects structural inequalities present from day one of the pandemic—March 19, 2020—the day Governor Newsom ordered California to close down.

As the pandemic raged through California for the past year, these structural inequalities offered more and more opportunities for the coronavirus to find its way into these populations. Each group has its own unique experience of structural inequality, so each group’s experience needs to be understood on its own terms

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture (CESLAC) at UCLA has provided reports on these inequalities experienced by the state’s various R/E groups, on topics ranging from greater exposure to the virus in the workplace to crowded housing and lack of health insurance. These reports are available on the CESLAC website:

These structural inequalities have been present for years—some for nearly 170 years (e.g., being under-served by public and private health services). If these structural inequalities are not remedied, the next pandemic will have the same disproportionate, tragic outcome for the populations that supply so many essential workers to the state’s economy.

The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, founded in 1961, is dedicated to enhancing the public's health by conducting innovative research, training future leaders and health professionals from diverse backgrounds, translating research into policy and practice, and serving our local communities and the communities of the nation and the world. The school has 631 students from 26 nations engaged in carrying out the vision of building healthy futures in greater Los Angeles, California, the nation and the world.

Faculty Referenced by this Article

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program

Dr. Joseph Davey is an infectious disease epidemiologist with over 20 years' experience leading research on HIV/STI services for women and children.

Dr. Anne Rimoin is a Professor of Epidemiology and holds the Gordon–Levin Endowed Chair in Infectious Diseases and Public Health.

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.