Love at first bite? Not for school kids and their vegetables

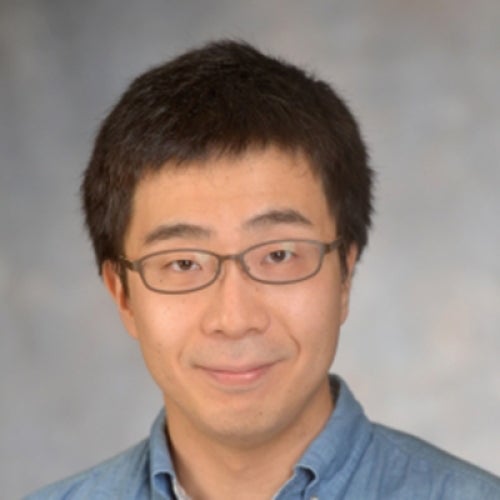

A new study from FSPH professor William McCarthy reveals that many school-provided fruits and vegetables are being discarded by LAUSD students.

Cajoling, pleading, even blackmail — just a few of the tactics parents have used when their children refuse to eat vegetables they haven't tried before. Now it appears that the nation's second largest school district is facing the same problem.

The Los Angeles Unified School District, which serves more than 650,000 meals each day, has become a national leader in offering healthy foods to its students. In September 2011, LAUSD launched a new lunch menu that features a variety of more wholesome food items, including fruits and vegetables, whole grains, vegetarian items and a range of healthy ethnic foods.

Two months after the new menu was introduced, researchers from UCLA and the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health wanted to understand how students were responding to the new offerings. Their research, conducted at four Los Angeles schools, found that many children didn't eat even a bite of the new, healthier items.

William McCarthy, a professor of health policy and management at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, and colleagues, measured the quantities of food left unselected in cafeteria food lines and the amount of food left over on students' lunch trays. Almost 32 percent of students in the cafeteria lines did not select fruit, and almost 40 percent did not select vegetables. Among those who did select a fruit or vegetable, 22 percent threw away the fruit and 31 percent tossed vegetable items, without eating a single bite. Boys consistently threw away more fruit and vegetables away without tasting them than did girls.

The results appear in the current online edition of the journal Preventive Medicine.

"Eating a variety of fruits and vegetables every day is essential for optimal health, and implementing changes to school menus, as has been done by the LAUSD, is an important first step to increasing students' repertoire of acceptable fruits and vegetables," said McCarthy, the study's co-senior author. "But increasing students' consumption of fruits and vegetables is clearly a challenging task. Given the rising rates of obesity among children in this country, getting students to expand their range of acceptable fruits and vegetables is an important goal."

Information about production waste — the food prepared in the school kitchen and left over after all students had been served — was obtained using LAUSD electronic records maintained for breakfasts, snacks and lunches. Data on so-called plate waste — the food, plastic wrap and cardboard packages that students left on their plates — were collected each day for five consecutive days at each school from a total of more than 2,000 middle school students. Students were asked to leave their trays at one of two staffed stations, where the amount of waste was recorded, and researchers noted students' perceived gender and ethnicity. Food waste also was bagged and weighed.

McCarthy said it's important for students to be more receptive to eating fruits and vegetables — and not just by drinking fruit juice — and that they need to be "primed" to accept menu changes like the LAUSD's. One strategy that has been proven to be effective is engaging students in the effort, especially boys.

Among the researchers' recommendations:

- Involving students in designing new menu options that use fruits and vegetables

- Offering a greater variety of fruits and vegetables to choose from

- Holding recess or physical education classes before lunch to increase

students' level of physical activity and, in turn, their hunger for

water-rich fruits and vegetables - Encouraging students to participate in a school-based gardening

program - Implementing a marketing campaign to promote the new food itemshttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.013

"Given that children consume up to half of their daily nutrients in school, school foodservice departments can have a powerful influence on increasing students' liking for healthier foods," McCarthy said, adding that it can take eight to 12 tastings for children to overcome their initial dislike of a new vegetable.

"Schools need to be patient and tolerate some plate waste … but students will not expand their liking for fruits and vegetables if they don't at least taste the food," he said.

The idea of spending money on food that goes to waste can be a challenge for schools, but McCarthy said exposing all students, including those from poor families, to healthy eating practices is the more important societal goal. "Today's food waste is the forerunner to tomorrow's healthy eating and therefore is a worthwhile investment," he said.

Other authors on the study were Tony Kuo of UCLA, and Lauren Gase and Brenda Robles of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. The analysis was conducted as part of program assessment activities at the LACDPH. Funding was also provided by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cooperative agreement (1U58DP002485-01) and a National Institutes of Health grant (1P50HL105188).

The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, founded in 1961, is dedicated to enhancing the public's health by conducting innovative research, training future leaders and health professionals from diverse backgrounds, translating research into policy and practice, and serving our local communities and the communities of the nation and the world. The school has 650 students from more than 35 nations engaged in carrying out the vision of "building healthy futures in greater Los Angeles, California, the nation and the world."

Faculty Referenced by this Article

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program

Dr. Anne Rimoin is a Professor of Epidemiology and holds the Gordon–Levin Endowed Chair in Infectious Diseases and Public Health.

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

Dr. Joseph Davey is an infectious disease epidemiologist with over 20 years' experience leading research on HIV/STI services for women and children.