First Class

Through courses taught by FSPH faculty, undergraduates are introduced to the foundations of public health and its potential to transform communities.

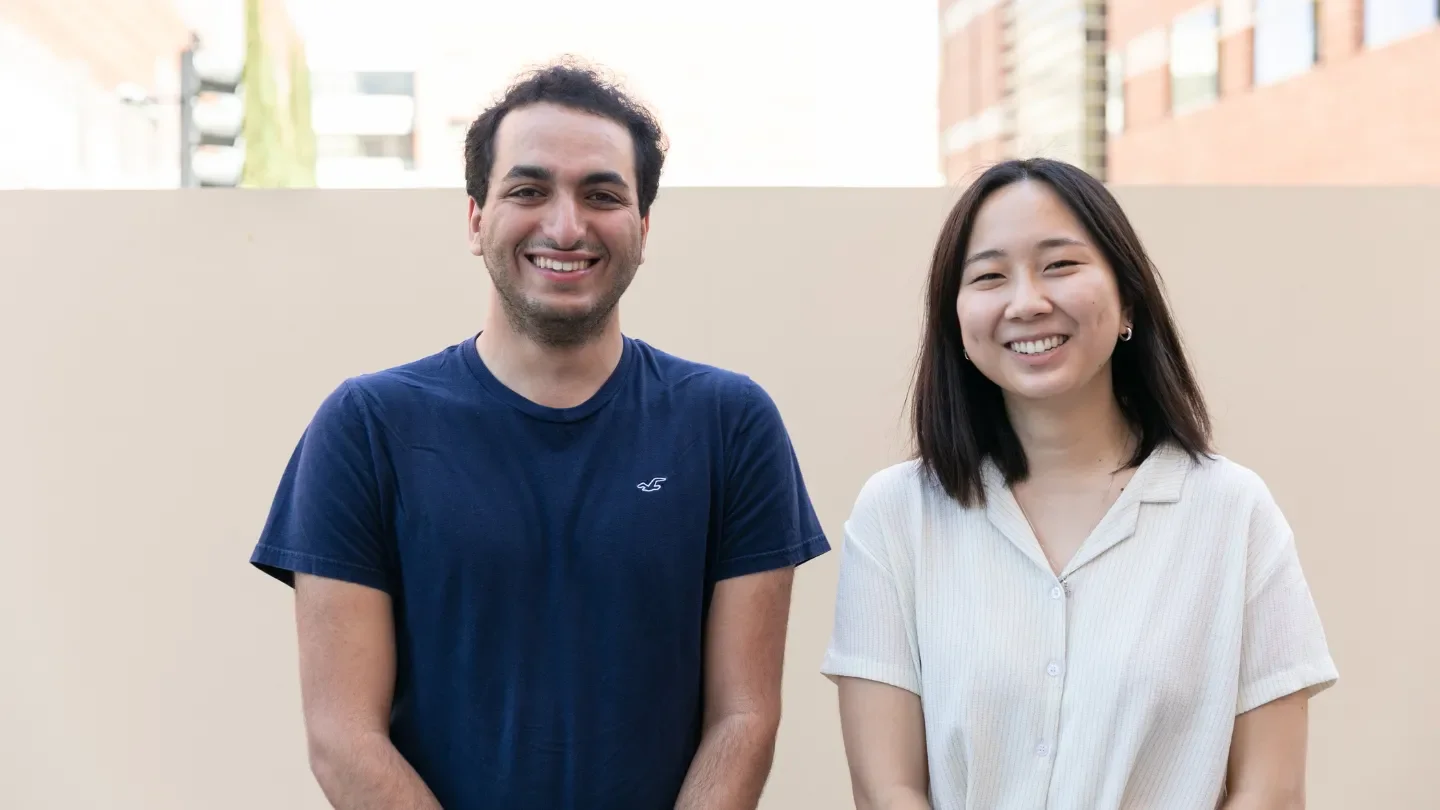

When Grant Cho entered UCLA as an undergraduate, he was on the pre-med track. But in Cho’s second year, a friend introduced him to Public Health Initiative: Leaders of Tomorrow (PILOT), a student-run organization for UCLA undergraduates interested in learning about public health. “That got me to realize that a health career didn’t have to involve one-on-one clinical interventions,” Cho says. “I found out UCLA had a public health minor, and quickly realized this was the field for me.”

Cho’s interest continued to grow as he learned about public health through the undergraduate courses taught by UCLA Fielding School of Public Health faculty. He went on to serve as president of PILOT for two years, helping to facilitate a series of career panels, networking events, and mentorship pairings involving UCLA undergraduates and UCLA Fielding students. Now he is an MPH student in UCLA Fielding’s Department of Health Policy and Management, where he’s learning about issues related to disparities in access to quality healthcare, particularly affecting immigrant populations, that he hopes to address in his public health career.

UCLA’s public health minor, offered since 2003, requires a minimum of seven courses, taught by faculty from each of FSPH’s five departments. With mounting recognition of public health’s importance in the era of COVID-19, climate change, and the reckoning with inequities driven by structural racism, the number of applications spiked — up more than 70% in the five years from 2015-16 to 2020-21. Moreover, many UCLA undergraduates enroll in public health courses even when not fulfilling requirements for the minor. “Our school has been deeply engaged in undergraduate education,” says Dr. Kyle McJunkin, FSPH’s assistant dean for academic programs. He notes that in the last five years, the school has substantially increased both the number of undergraduate courses offered and the student capacity in those courses. Often, students use the FSPH-taught courses to fulfill the requirements for their major, or for other minors. For example, CHS 48, Nutrition and Food Studies: Principles and Practice, a popular undergraduate course taught by Dr. May Wang, FSPH professor of community health sciences, is taken by students pursuing UCLA’s food studies minor.

McJunkin points out that because public health isn’t a topic typically addressed in the high school curriculum, exposing students to the field before they have made career or graduate-school decisions is critical to drawing passionate, bright individuals to the profession. To that end, beginning this fall, for the first time FSPH will offer two new undergraduate courses geared toward first- and second-year students — PH 50A and B, taught by Dr. Robert Kim-Farley (MPH ’75), professor in the departments of epidemiology and community health sciences. PH 50A will provide a foundational introduction to the field of public health, Kim-Farley notes, while PH 50B, taught in the winter, will offer an introduction to contemporary public health issues.

Although Noah Danesh has always intended to apply to medical schools after earning his undergraduate degree, he discovered the public health minor and decided learning about topics such as health policy and management, along with biostatistics, would provide a strong foundation. Fulfilling the minor’s requirements gave him a better understanding of shortcomings in healthcare for underserved communities, Danesh says. “Now, going into medicine, I recognize that having the lens of public health is essential to viewing and solving the problems of these communities holistically,” he explains.

As COVID-19 was just starting its global spread in early 2020, Victoria Li took an introductory public health course taught by Kim-Farley. Like Danesh, Li is a pre-med student, but the class convinced her that the minor was an ideal complement to her pre-med courses, and now she’s considering pursuing an MPH as well as an MD after she graduates. “It was a unique experience living through the beginning of COVID and hearing in real time from someone who was an expert in what was going on,” says Li, who was recently chosen to serve as editor in chief of the Daily Bruin, UCLA’s campus newspaper. She and Danesh, who has written on science and health for the publication, say they have incorporated what they’ve learned from the public health minor in their journalism.

While many of the undergraduates who enroll in the FSPH-taught courses end up pursuing public health graduate education and careers, Dr. Ron Brookmeyer, dean of the UCLA Fielding School and distinguished professor of biostatistics, says introducing public health to undergraduates brings benefits regardless of the students’ career trajectory. “We are committed to increasing public health literacy throughout the campus, and that can take different forms,” Brookmeyer says. “These students are learning about the importance of prevention, health equity, and a population-based approach to solving problems, and that’s going to be a valuable perspective no matter what profession they choose.”

Katherine Brenner was thinking of becoming a clinical psychologist when she enrolled in Epi 100 because of her interest in diseases. From there she took PH 150, an introduction to public health issues taught by Kim-Farley, and decided to continue with the public health minor. In the fall Brenner will start a PhD program in environmental engineering at UC Irvine. She is interested in focusing on water sanitation issues in low-income countries, given the potential impact on large populations. “I didn’t realize there was this whole health career field outside of being a doctor,” Brenner says. “I’ve always wanted to work abroad, so learning about Dr. Kim-Farley’s experiences was fascinating to me.”

Kim-Farley embodies both the many career possibilities and public health’s potential to touch millions of lives. A physician board-certified in public health and preventive medicine, he started his career with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Epidemic Intelligence Service, traveling to different countries to fight infectious disease outbreaks. He spent about two decades with the World Health Organization (WHO) in positions that included regional adviser for immunization programs for Southeast Asia, director of the global immunization program in Geneva, Switzerland, and head of the WHO for Indonesia and India. He then returned to Los Angeles, where he served 13 years as director of communicable disease control and prevention for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health before transitioning to fully devoting his time to teaching and mentoring students as a member of the UCLA Fielding School faculty.

Having accomplished so much in his career, Kim-Farley could have retired, but he gets a special satisfaction from teaching undergraduates. “It’s exciting to me as a professor to see students who have not been exposed to this field say, ‘I had no idea of the range and scope of public health,’” Kim-Farley says. “My purpose now is to pay it forward to inspire the next generation of public health professionals — and, for the students who don’t go into public health, to make sure they have an appreciation for the fact that there are people working with the community as their patient, and that this approach to health can make a huge difference.”

Faculty Referenced by this Article

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Dr. Anne Rimoin is a Professor of Epidemiology and holds the Gordon–Levin Endowed Chair in Infectious Diseases and Public Health.

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.

Director of Field Studies and Applied Professional Training

Dr. Joseph Davey is an infectious disease epidemiologist with over 20 years' experience leading research on HIV/STI services for women and children.

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Assistant Dean for Research & Adjunct Associate Professor of Community Health Sciences

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.

Automated and accessible artificial intelligence methods and software for biomedical data science.