UCLA research finds that U.S. sick leave policies widen racial inequalities, lag nearly every other country

Paid sick leave is a powerful tool for preventing the spread of COVID-19 & infectious diseases & ensuring all workers can access treatment.

Paid sick leave is one of the most powerful tools for preventing the spread of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases and ensuring all workers can access treatment—yet tens of millions of workers across the U.S. lack coverage.

Today, the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health's WORLD Policy Analysis Center (WORLD) released the first study to systematically analyze how common sick leave eligibility criteria in the U.S. affect access and to examine sick leave policies globally to understand whether these criteria are necessary. The research found marked racial and gender gaps in leave access in the U.S. due to restrictions targeting workers at small businesses, part-time workers, and workers at new jobs.

“People of color have faced higher risks of exposure to COVID-19 due to inequalities in working conditions, higher rates of serious illness due to environmental inequalities, and higher risks of financial devastation due to job losses compounded by longstanding racial wealth gaps created by U.S. policies,” said Dr. Jody Heymann, a UCLA distinguished professor of public health, public policy, and medicine who serves as director of WORLD. “The U.S.’s lack of paid sick leave for all—and disparities in access worsened by eligibility rules—only further entrench this crisis.”

The study found that in the private sector, 18.7% of Latina women, compared to just 8.4% of white men, lack access to the unpaid leave provided by the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) because of its minimum annual hours requirement. Requiring one year with the same employer excludes higher shares of Black (22%), Indigenous (22.9%), and self-identified multiracial (27.7%) workers than white workers (19%).

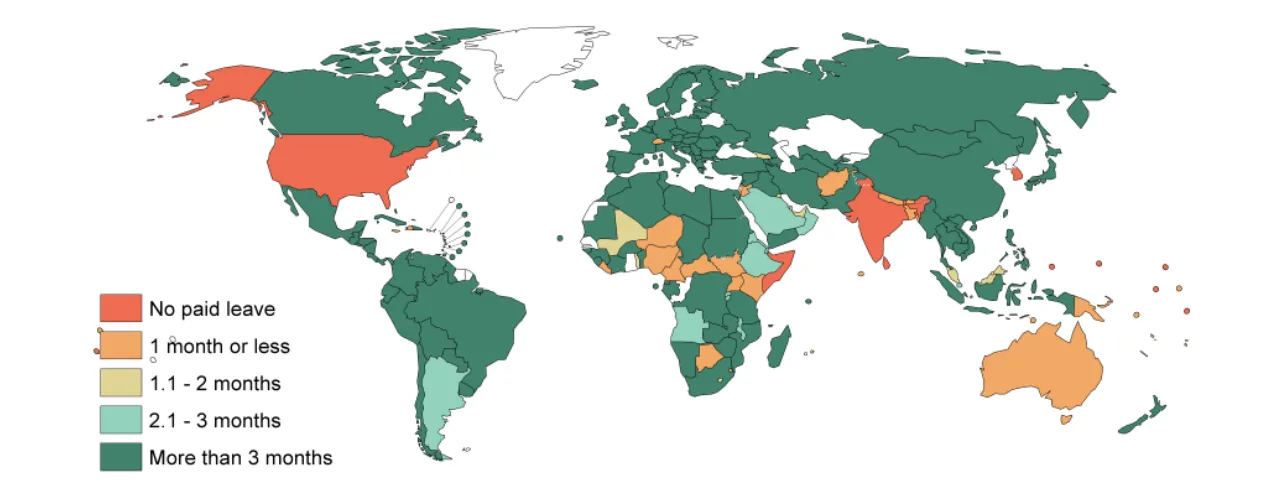

Further, the study found that nearly all countries globally have demonstrated the feasibility of closing these gaps by making leave available without broad restrictions based on firm size (100% of countries that provide paid sick leave), minimum hours of work (93%), or tenure (96% cover workers with less than a year of tenure or contributions— more than half of which cover workers regardless of employment history).

Heymann is lead author of the study, “U.S. Sick Leave in Global Context: US Eligibility Rules Widen Inequalities Despite Readily Available Solutions,” published in Health Affairs. To understand the implications of common eligibility restrictions that have been included in state- and city-level sick leave laws as well as proposals to adopt leave nationally, her team measured the impacts of the minimum firm size, tenure, or hours requirements in the FMLA, which provides unpaid leave for serious medical conditions. The team then systematically coded the eligibility rules for sick leave in every other U.N. member state to understand whether these criteria were common or necessary.

“These rules are not discriminatory on their face,” said Aleta Sprague, senior legal analyst at WORLD. “Yet when layered on top of deep inequalities in the labor market, they have discriminatory effects—and we need to be anticipating and avoiding those impacts when designing policy.”

Some rules also exclude high shares of workers overall, the study found: over a third of the private sector workforce, including 42% of Latinx workers, 35.9% of white workers, and 24.4% of Black workers, work for an employer with fewer than 50 employees, making them ineligible for the FMLA. Latino men face the highest rate of exclusion by this rule, at 45%.

Moreover, the FMLA is not an outlier: similar types of eligibility criteria are found in leave policies and proposals at all levels. For example, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act adopted the same 50-employee threshold to limit access to family leave during the pandemic, while many states and cities that have adopted paid sick or medical leave—from Connecticut to Tacoma to Dallas to Maryland—have included their own exclusions based on hours, firm size, tenure, and/or type of employment.

“These exclusions vastly undercut the potential of current and proposed leave policies to reach everyone,” said Alison Earle, principal research analyst at WORLD. “But by addressing the gaps that we know worsen racial and ethnic inequalities in access, we will also substantially improve coverage overall—with powerful benefits for both public health and families’ economic wellbeing.”

The study’s global data makes clear that providing paid sick leave to all workers is readily achievable. For example, among the 181 countries that guarantee paid sick leave globally, none broadly exclude workers based on the size of their employer. Further, 68% of high-income countries explicitly cover the self-employed, creating a mechanism to cover vulnerable own-account workers and potentially reach many in the gig economy—a group common excluded from key social security and labor protections.

“It’s critical to recognize that covering everyone is not only necessary but eminently feasible,” said Willetta Waisath, senior research analyst at WORLD. “For example, when we look at the global data, we see that the vast majority of countries that have adopted paid sick leave make it available without a minimum hour requirement.”

Indeed, only 4% of the high-income countries with paid sick leave require workers to work a minimum number of hours to qualify, the study found. Fully covering part-time workers is both critical to racial and gender equity and to maximizing the public health benefits of sick leave.

“During every infectious outbreak of the past two decades—from SARS to H1N1 to MERS—Congress has considered but ultimately failed to adopt permanent paid sick leave,” Heymann said. “Missing the opportunity to do so now would have health and economic consequences that far outlast the pandemic. But the details matter: only by ensuring we design our paid leave policies to reach every worker can we protect public health and take one important step toward rectifying the longstanding and devastating racial and socioeconomic inequalities that have only intensified during this pandemic.”

Methods: We analyzed a nationally representative survey to determine the extent to which specific FMLA features produce gaps and disparities in leave access. We then use comparative policy data from 193 countries to analyze whether these policy features are necessary or prevalent globally, or whether there are common alternatives.

Data availability statement: All data analyzed are publicly accessible through the WORLD Policy Analysis Center Datasets at http://worldpolicycenter.org/

The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, founded in 1961, is dedicated to enhancing the public's health by conducting innovative research, training future leaders and health professionals from diverse backgrounds, translating research into policy and practice, and serving our local communities and the communities of the nation and the world. The school has 631 students from 26 nations engaged in carrying out the vision of building healthy futures in greater Los Angeles, California, the nation and the world.

Faculty Referenced by this Article

Nationally recognized health services researcher and sociomedical scientist with 25+ years' experience in effectiveness and implementation research.

Dr. Ron Andersen is the Wasserman Professor Emeritus in the UCLA Departments of Health Policy and Management.

EMPH Academic Program Director with expertise in healthcare marketing, finance, and reproductive health policy, teaching in the EMPH, MPH, MHA program

Robert J. Kim-Farley, MD, MPH, is a Professor-in-Residence with joint appointments in the Departments of Epidemiology and Community Health Sciences

Industrial Hygiene & Analytical Chemistry

Director of Field Studies and Applied Professional Training

Dr. Michelle S. Keller is a health services researcher whose research focuses on the use and prescribing of high-risk medications.

Associate Professor for Industrial Hygiene and Environmental Health Sciences

Professor of Community Health Sciences & Health Policy and Management, and Associate Dean for Research

Dr. Joseph Davey is an infectious disease epidemiologist with over 20 years' experience leading research on HIV/STI services for women and children.

Automated and accessible artificial intelligence methods and software for biomedical data science.

Dr. Hankinson is a Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and of EHS, and Chair of the Molecular Toxicology IDP

Dr. Anne Rimoin is a Professor of Epidemiology and holds the Gordon–Levin Endowed Chair in Infectious Diseases and Public Health.

Assistant Dean for Research & Adjunct Associate Professor of Community Health Sciences